Wordcounts in starting research--what do we have now?

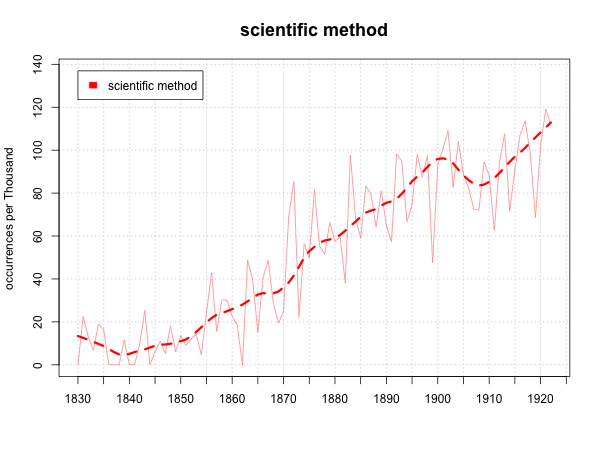

All right, let’s put this machine into action. A lot of digital humanities is about visualization, which has its place in teaching, which Jamie asked for more about. Before I do that, though, I want to show some more about how this can be a research tool. Henry asked about the history of the term ‘ scientific method. ’ I assume he was asking a chart showing its usage over time, but I already have, with the data in hand, a lot of other interesting displays that we can use. This post is a sort of catalog of what some of the low-hanging fruit in text analysis are.

The basic theory I’m working on here is that textual analysis isn’t necessarily about answering research questions. (It’s not always so good at doing that.) It can also help us channel our thinking into different directions. That’s why I like to use charts and random samples rather than lists–they can help us come up with unexpected ideas, and help us make associations that wouldn’t come naturally. Essentially, it’s a different form of reading–just like we can get different sorts of ideas from looking at visual evidence vs. textual evidence, so can we get yet other ideas by reading quantitative evidence. The last chart in the post is good for that, I think. But first things first: the total occurrences of “scientific method” per thousand words.

This is what we’ve already had. But now I’ve finally got those bookcounts running too. Here is the number of books per thousand* that contain the phrase “scientific method”:

Well, it increases, but the numbers are quite small–.001 per thousand is an order of magnitude less than a lot of the patterns we’ve been looking at. The most citations is 218 in 1902 (the spike in 1885 has 188 occurrences, in a year that I have fewer books for). So we can’t look for the invention of the scientific method in 1880s, but we can look at its popularization and changing meanings. If this was a flat line, the study would probably do better to focus on changing meanings than on popularization, because the evidence would be it didn’t get all that much popular.

The bookcounts graph gives something of the same story, but it tells more of a story of gradual increase from around 1850, rather than from around 1870 as the wordcounts might lead us to think. I need to think about why this is–I think there’s an easy mathematical explanation, but I’m tired.

So that’s something. We might want to compare it to some other movements, look up some of the spikes–it looks like there was a book or two in 1885 that used the phrase lots of times–and see if other words have that decline from 1900 to 1910.

What else can we do? Well, we can see what words are used in connection with it. The words that appear in a sentence with “scientific method” don’t tell us very much:

the of and to scientific

17359 13708 7545 6346 5538

in a method is that

5105 3708 3687 3128 2606

A bunch of common words, and the two constituent words. The only remotely surprising fact is that scientific appears much more often than method–but that’s just because my code counts the phrase “scientific methods” as well.

If we divide those by the overall totals and multiply by 100, we start to get something interesting:

scientific method of is in

3.012 0.982 0.010 0.009 0.007

That tells us that 3 percent of all occurrences of the word “scientific” are in the same sentence as the phrase “scientific method,” and 1% of all occurrences of “method.” Maybe we want a new count to see what other kinds of methods there are. Clearly the rest of the words have no particular tie. But we can apply the same method to all the words that appear in a sentence with scientific method:

phenomenism inseparability irrefragably

6.19 4.12 3.59

philosophized scientific eealism

3.04 3.01 2.81

positivism presuppositions ideological

2.52 2.34 2.29

josselyns attika reorganizes

2.23 2.22 2.21

Those are some obscure words. Some of them are probably just chance or the results of very small groups talking with each other–‘ irrefragably ’, which means ‘ indisputably ’, appears just 7 times in a sentence with scientific method, and some of those are probably multiple editions of a text. Our number one hit, though, “phenomenism”, happens 21 times with scientific method, and 339 overall–sounds worth checking out. (I can’t remember whether I ever came across that term in reading about the history of phenomenalism). And positivism is obviously an important movement in the late 19C to check out for the origins of anything scientific, though I don’t know my mind would take me there right away. If we require a minimum number of hits, we get “Comte” and the names of a couple social sciences. Not bad.

But while before we were just getting a list of common words, now we’re just getting words that themselves use ‘ scientific method ’ all the time. Our phrase is important to them–but are they important to our phrase? Time for a scatterplot. We’ll put the words that are important for scientific method (‘ the ’,’of’,and so on) on one axis and the words that scientific method is important to (phenomenism, inseparability, etc., on the other). The first pass will just illustrate the numbers I showed above:

We’re interested in words that aren’t close to either of the axes, and the only words discernibly so are ‘ scientific ’,’method’,and ‘ methods ’. I’m not going to lead you through all the transformations, but I’m changing the axes so they’re on the same scale, and using logarithmic axes so we can pull more detail out. That makes the general scatter plot look like this, with the words we’ve been tracking written over it to help get your bearings:

Those striped bands on the left are words that only appear once along with our keyphrase; the next band is twice, and so on until we get to a reasonable sample somewhere around 20, where ‘ phenomenism ’ is. I also highlight a couple of the outliers on the bottom–“she”, “you”, and “her”are strikingly unlikely to appear in a sentence with “scientific method.” Those sorts of outliers can be interesting, though only when used with care. It might be interesting, say, to see if the language used by peddlers of scientific method is yet more male-centric than other forms of science writing. “Scientific”, “method”, and “methods” still stick out as the words for which we know the phrase is both important and has importance to. But now we can see a bunch of other suggestively positioned words out there to think about as well. Let’s zoom in on that portion of the graph, and write all words in.

So how useful is that? There’s certainly some interesting stuff to think about–the social sciences stick out far more than the hard sciences, Comte makes an appearance in the flesh, and so on. The working hypothesis I’d draw, which isn’t completely trivial, is that Comtean social science plays an role in the conceptualization of the scientific method during the period of its emergence in America. Drawing that isn’t completely mechanical–it requires me to know that Comte, the social sciences, and positivism all have strong links to each other. (I suppose we could program that in somehow, though–Comte, at least, would be proud.) But I might be completely wrong to seize on those–I’m dismissing the Francis Bacon words that stick out because I think that they (Bacon, Organon, etc.) are probably just throat-clearing in books or history, which is what the Comte stuff may be too. Someone with more knowledge may be able to see better patterns. Also, we might want to do a year-by-year exploration–I’ll leave that for another time. This post is already long, even by my standards.

We could also make these easier to read–I love word scatterplots, but they are ugly in their way. It would be pretty easy to code a metric of distinctiveness that gives the distance of any word from the axes–that way we could just get an ordered list in which “scientific” would be the first word, “method” the second, methods the third, and then some interesting stuff. I like having the dimensional data, though, easily accessible, and doing that right now is work.

What’s easy, though, is to reproduce that last chart for bookcounts. Instead just limiting ourselves to sentences, we can find out what words appear in the same _book_ as any discussion of scientific method. For the most part, that’s going to be more interesting because it works from a larger sample. Here are the 1500 of the 192,000 words that appear in books using the phrase “scientific method” that show the strongest correlation. Again, farther to the right are words that “scientific method” frequently uses, and farther up are words that usually appear alongside “scientific method”. I think Blogger lets you click on the thumbnail to get a large version of the full image, which you’ll need:

There’s more here than I could describe in a minute, so just a few impressionistic thoughts:

biology, sociology, and psychology are the words the farthest out. “Physics” and chemistry is actually used more often in the books mentioning the scientific method than the first two of these, but they gets pushed back into the cloud because books using physics don’t actually talk about the scientific method nearly as much as books using ‘ sociology. ’ Presumably this has to do with insecurities

Lots of famous scientists in the cloud. Most distinctively situated: Kant’s prominence shows how differently he was taught then than now. Darwin is as prominent as always. Hegel is somewhat surprising; Huxley is not.

In the upper left, the words that rely a lot of scientific method but are less important in scientific method’s prominence, are several education words–pedagogy, kindergarten, pedagogical, etc.

Now, if you’re not interested in the history of the scientific method, this isn’t interesting to you. But we can have the same plot for any other phrase (it takes computing time, but not much work), and I feel like for brainstorming, at least, about the connections of a given topic, these could be quite useful.

What they’re missing, tragically, is the temporal dimension. Any ideas on how to bring that back in? I’ve got a couple inchoate ones now.

Comments:

Ben this is great - lots of thoughts that will hav…

Anonymous - Nov 6, 2010

Ben this is great - lots of thoughts that will have to wait until tomorrow, but just wanted to toss out that portions of my writing on the matter have just been strongly buttressed! As it were! Hank