Typical TV episodes: visualizing topics in screen time

The most interesting element of the Bookworm browser for movies I wrote about in my last post here is the possibility to delve into the episodic structure of different TV shows by dividing them up by minutes. On my website, I previously wrote about story structures in the Simpsons and a topic model of movies I made using the general-purpose bookworm topic modeling extension. For a description of the corpus or of topic modeling, see those links.

In this post, I’m going to combine those two projects. What can we see by looking at the different content of TV shows? Are there elements to the ways that TV shows are laid out–common plot structures–that repeat? How thematically different is the end of a show from its beginning? I want to take a first stab at those questions by looking at a couple hundred TV shows and their structure. To do that, I:

Divided a corpus of 80,000 movies and TV show episodes into 3 minute chunks, and then divided each show into 12 roughly-equal parts.

Generated a 128-topic model where each document is one of those 3-minute chunks, which should help the topics be better geared to what’s on screen at any given time.

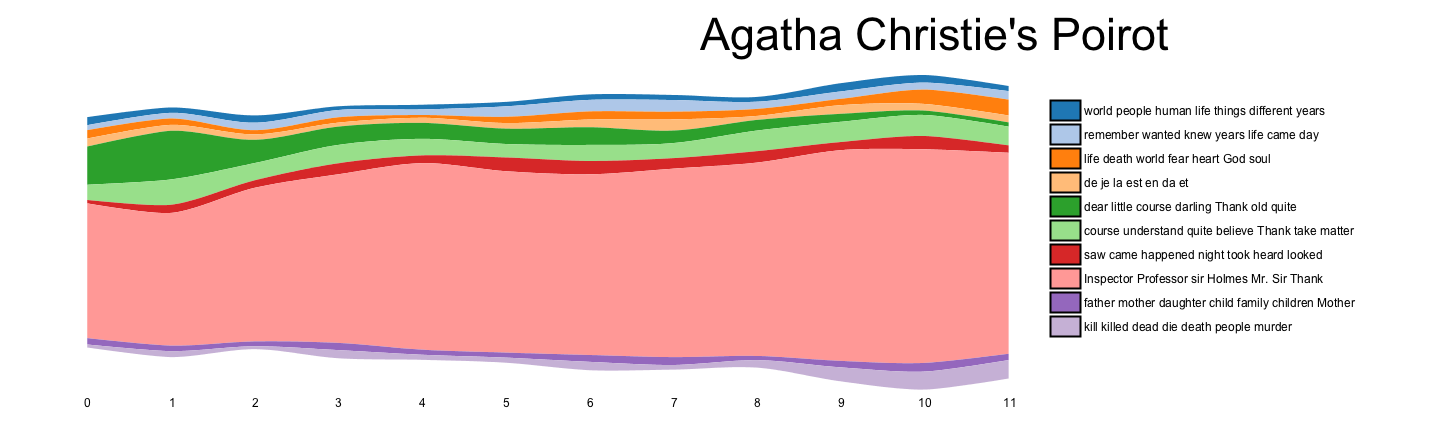

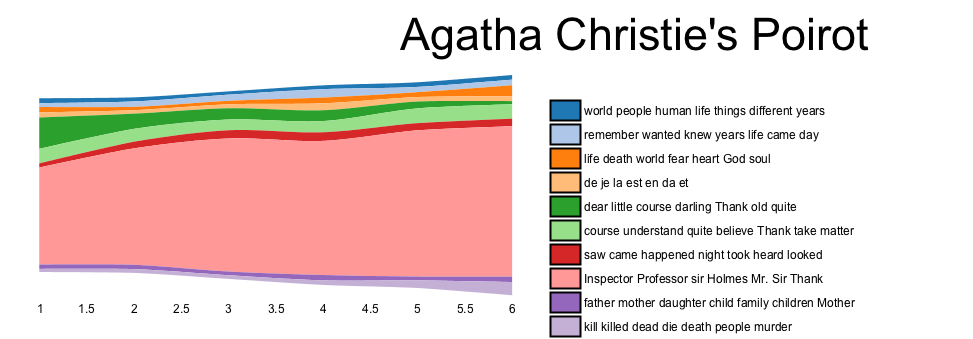

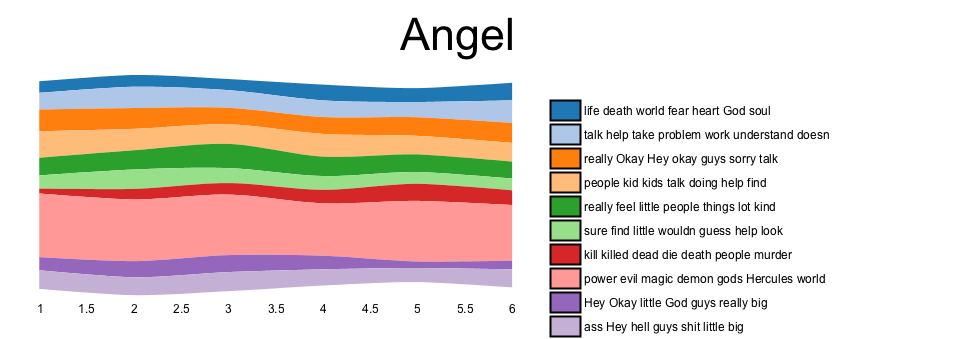

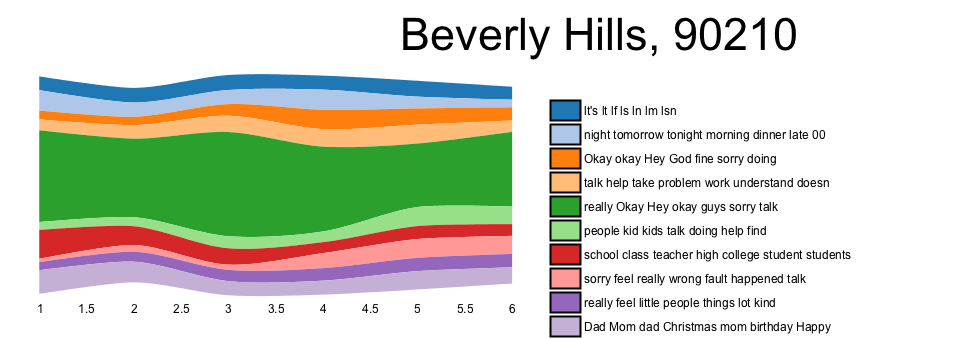

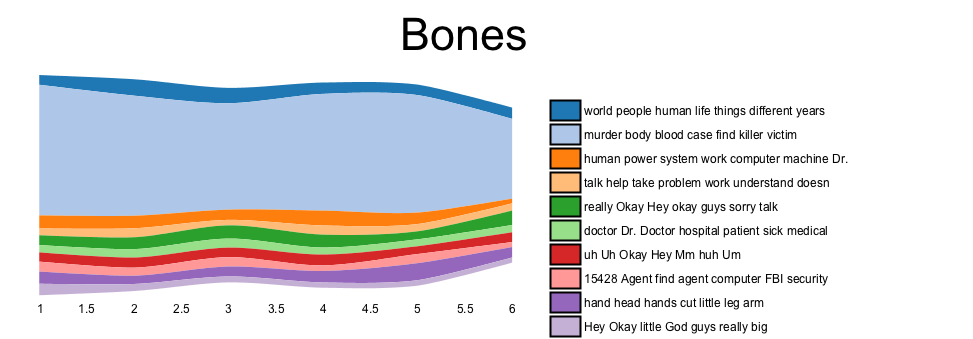

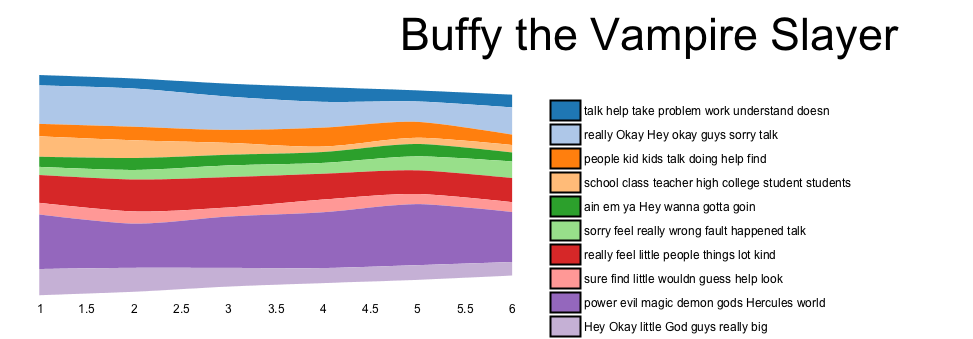

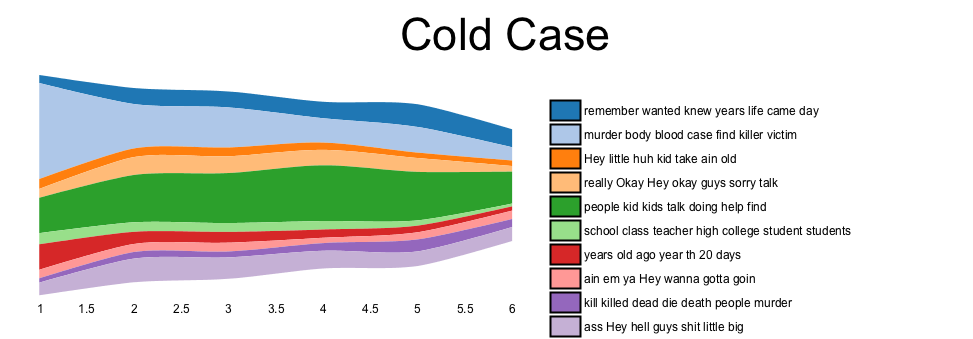

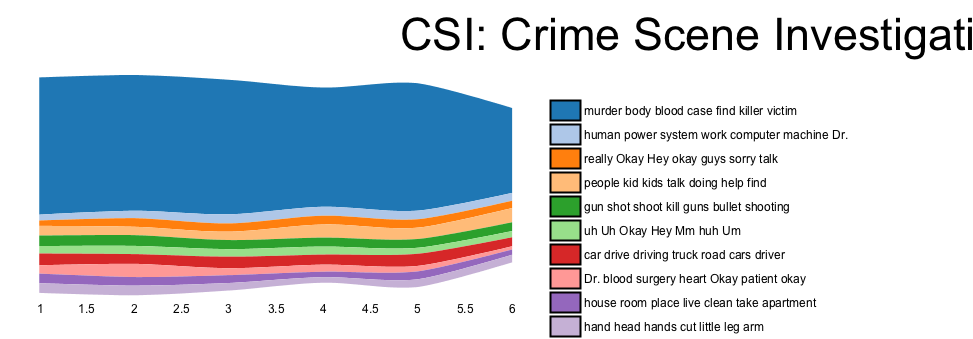

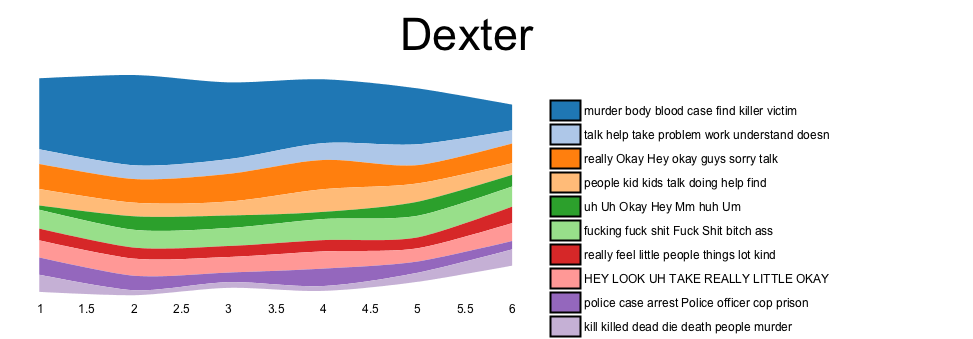

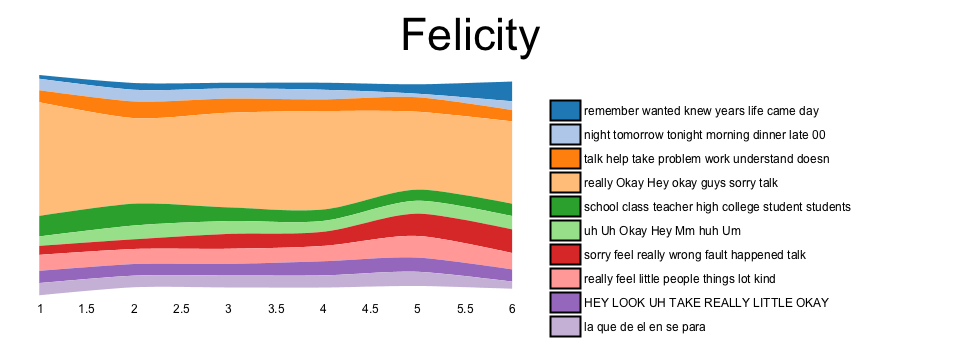

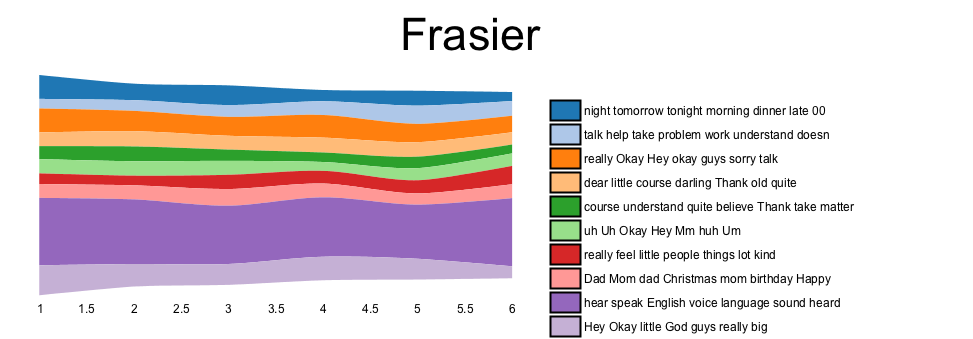

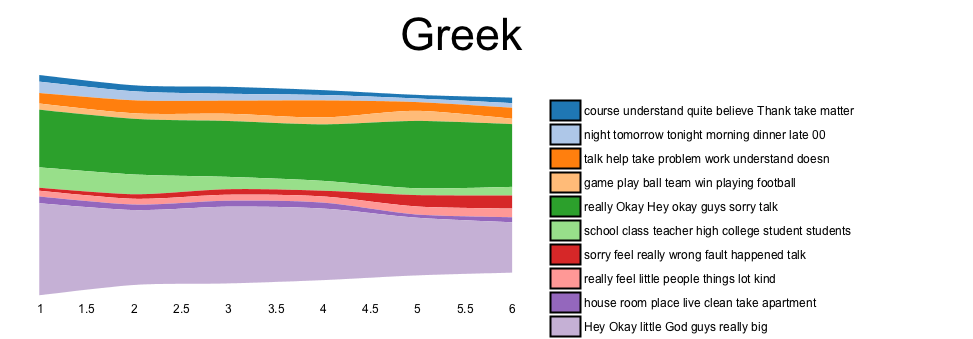

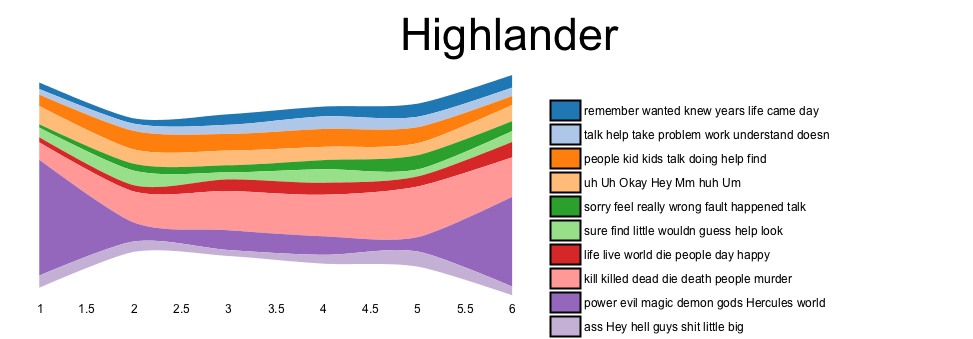

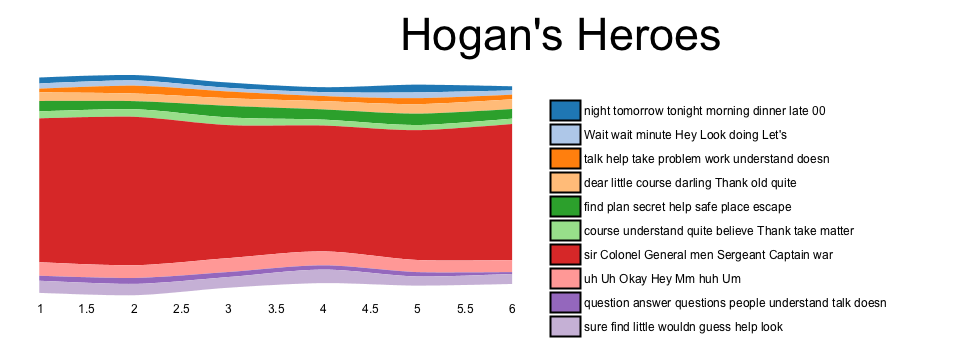

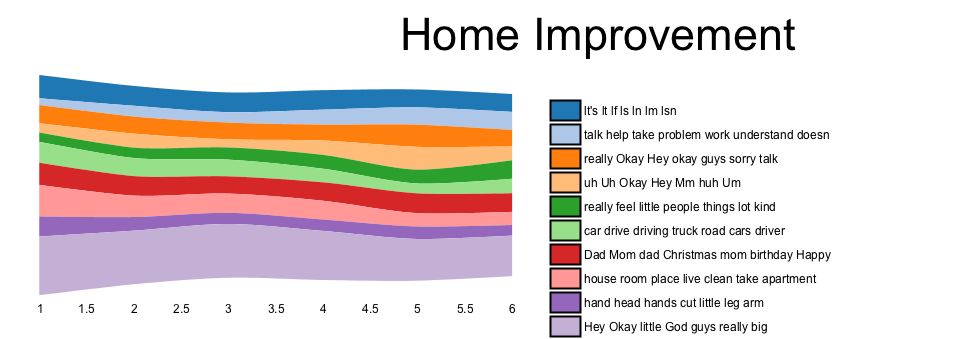

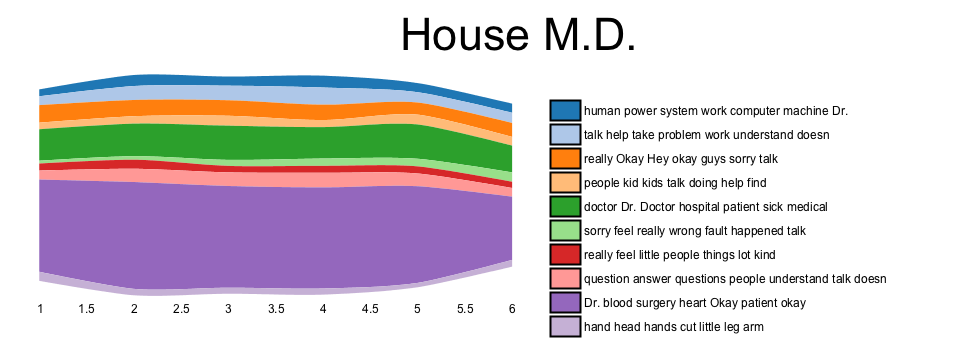

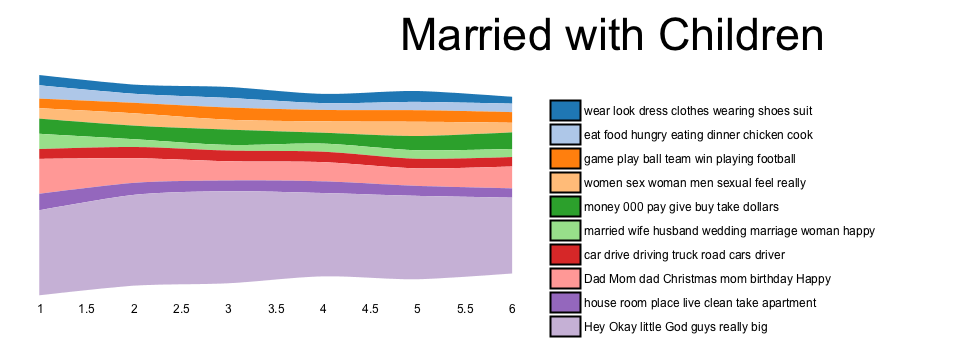

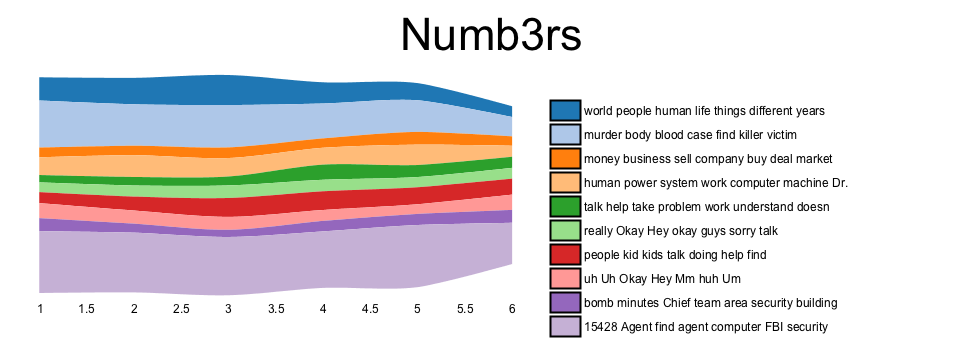

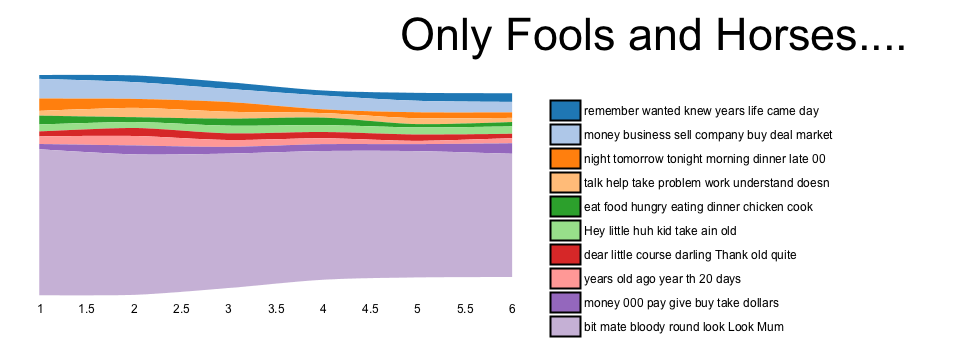

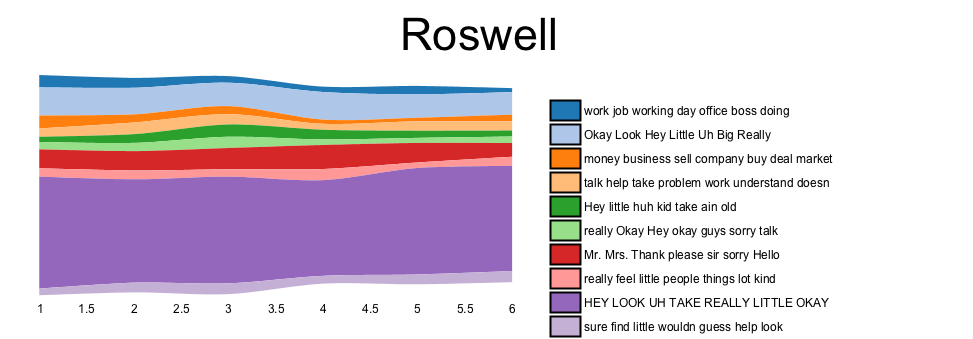

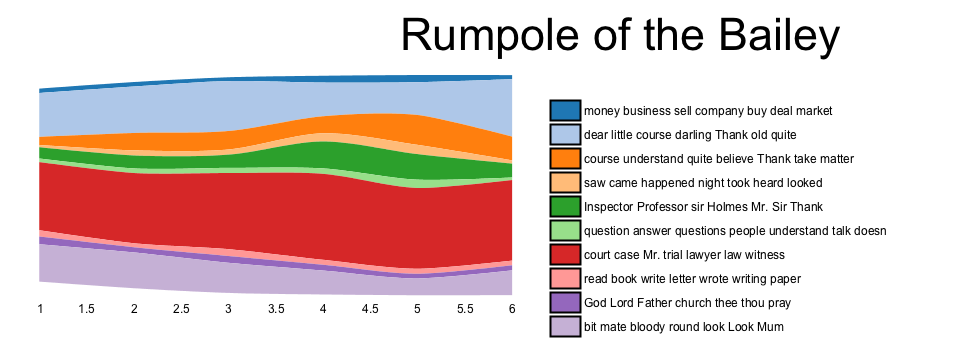

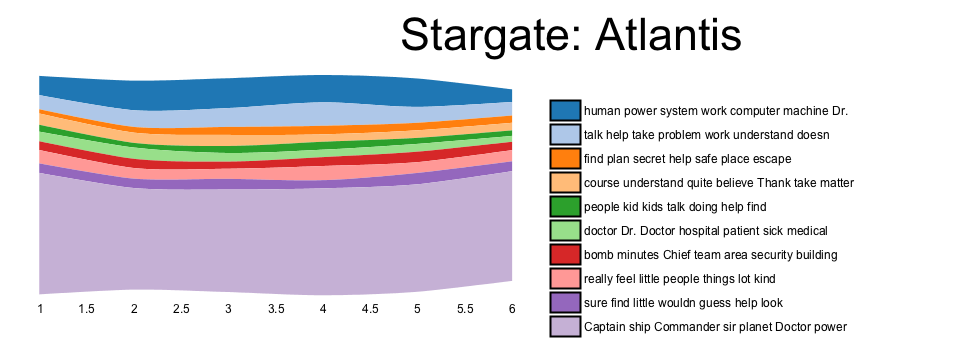

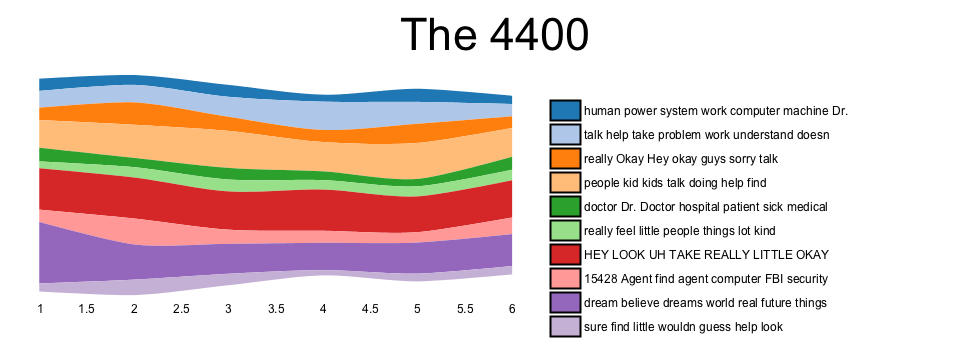

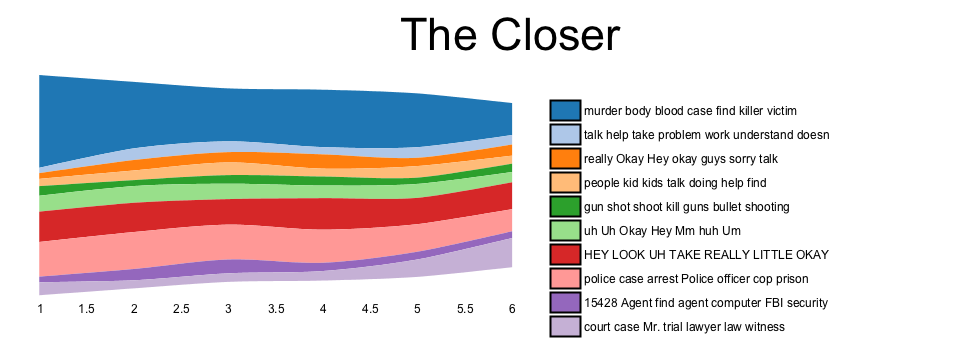

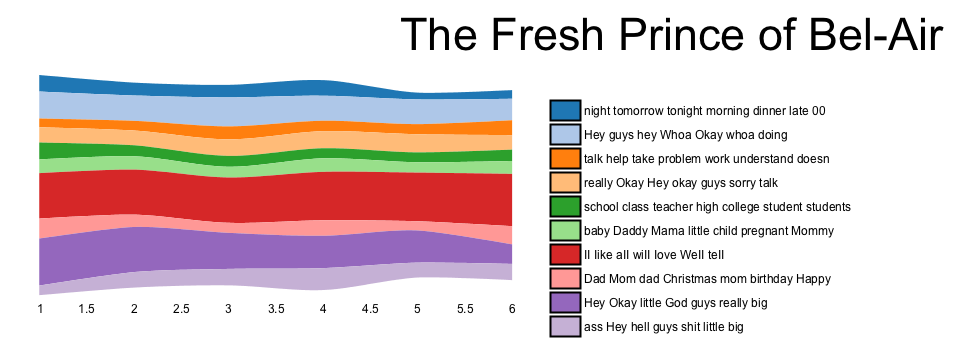

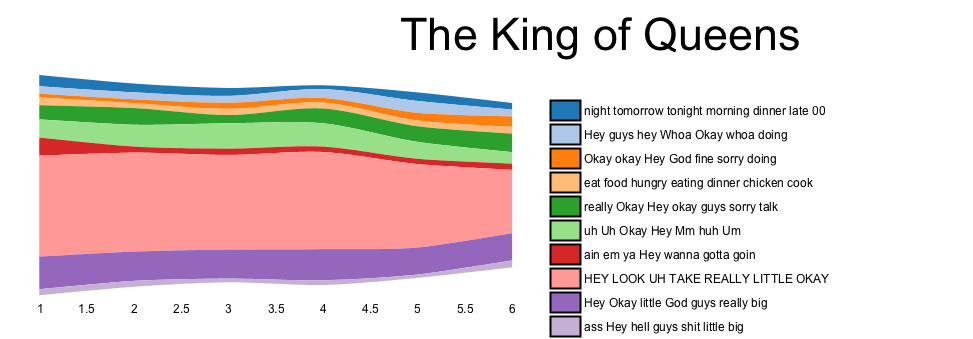

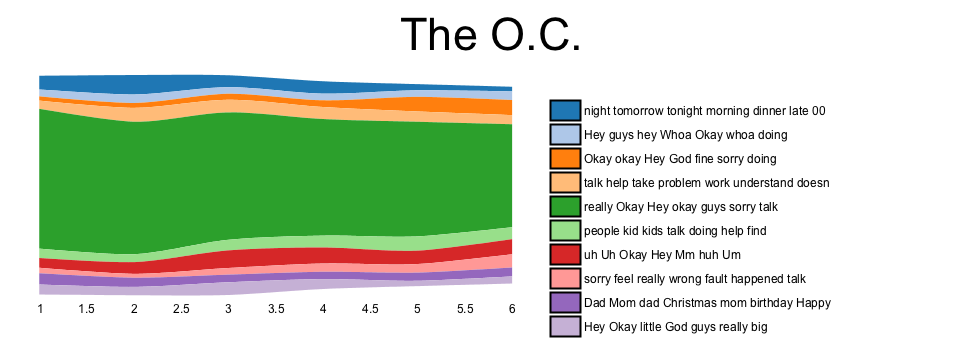

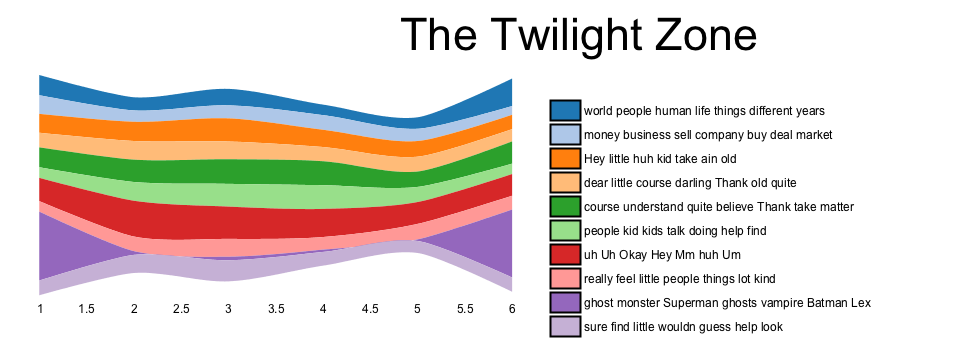

For every TV show, plotted the distribution of the ten most common topics with the y-axis roughly representing percent of dialogue of the show in the topic, and the x-axis corresponding to the twelfth of the show it happened in. So dialogue in minute 55 of a 60-minute show will be in chunk 11.

First a note: these images seem not to display in some browsers. If you want to zoom and can’t read the legends, right click and select “view in a new tab.”

Let’s start by looking at a particularly formulaic show: Law and Order.

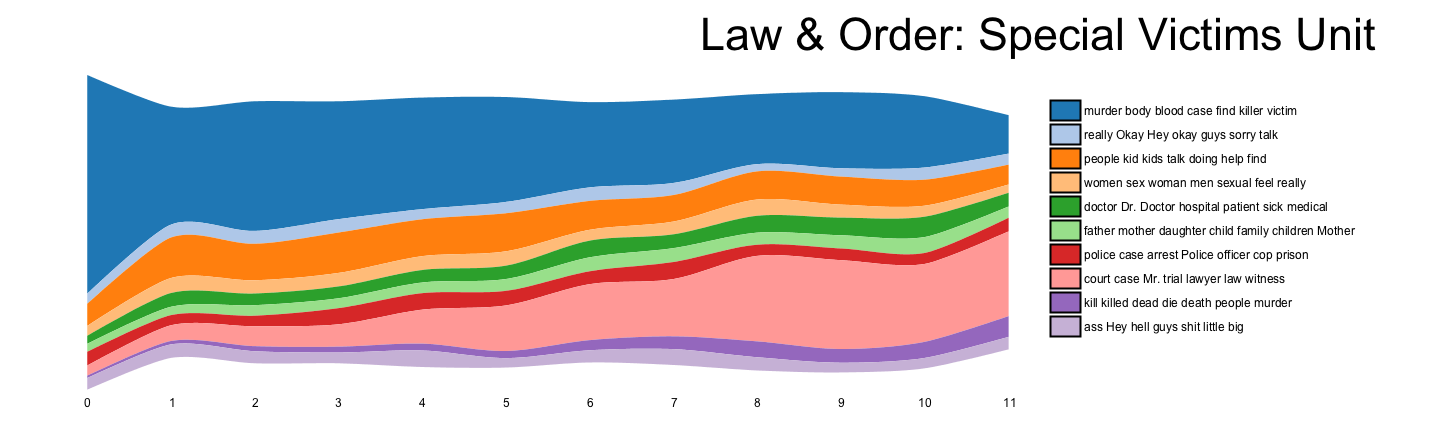

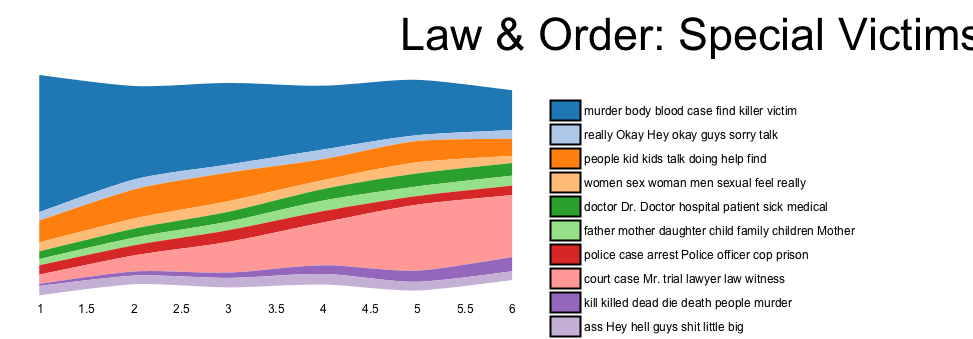

The two most common topics in Law & Order are “court case Mr. trial lawyer” and “murder body blood case”. Murder is strongest in the first twelfth, when the body is discovered; “court case” doesn’t appear in any strength until almost halfway through, after which it grows until it takes up more than half the space by the last twelfth.

That’s pretty good straight off: the process accurately captures the central structuring element of the show, which is the handoff from cops to lawyers at the 30 minute mark. (Or really, this suggests, more like the 25 minute mark). Most of the other topics are relatively constant. (It’s interesting that the gun topic is constant, actually, but that’s another matter). But a few change–we also get a decrease in the topic “people kid kids talk,” capturing some element of the interview process by the cops; a different conversation topic, “talk help take problem,” is more associated with the lawyers. Also, the total curve is wider at the end than at the beginning; that’s because we’re not looking at all the words in Law & Order, just the top ten out of 127 topics. We could infer, preliminarily, that Law and Order is more thematically coherent in the last half hour than the first one: there’s a lot of thematic diversity as the detectives roam around New York, but the courtroom half is always the same.

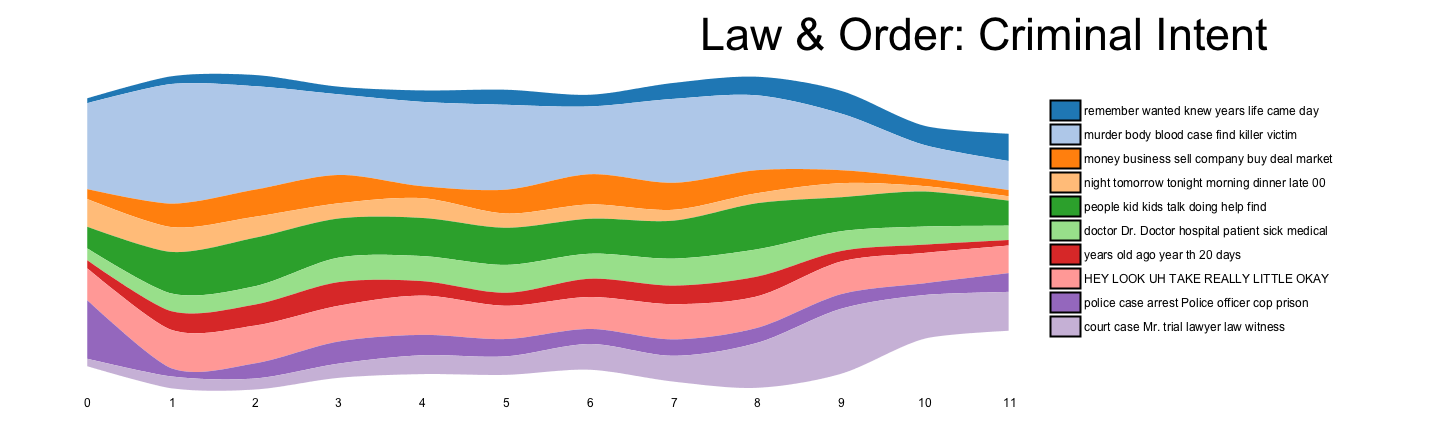

Compare the spinoffs: SVU is almost identical to the Law & Order mothership, but Criminal Intent gets to the courtroom much later and with less intensity.

See below the fold for more. Be warned: I’ve put a whole bunch of images into this one.

Some of the things revealed are interesting because they tell us when a show departs from its ostensible topic.

“Grey’s Anatomy” (which I’ve never seen) appears to open as a fairly strong hospital drama, but by the end the medical content has dropped by half. It’s not completely clear from the topics what’s replaced it, but topics like “sorry feel really” and “remember wanted knew” grow in strength, suggesting the soapier elements get stronger through an episode.

“Sex and the City” is similar, though less marked:the light green sex topic gets less significant through the course of the episode, though the smaller light orange “New York City” topic doesn’t change quite so much.

“Cheers” moves away from the bar through each episode, and into the language of apology: (this is broken into sixths rather than twelfths; see below for why).

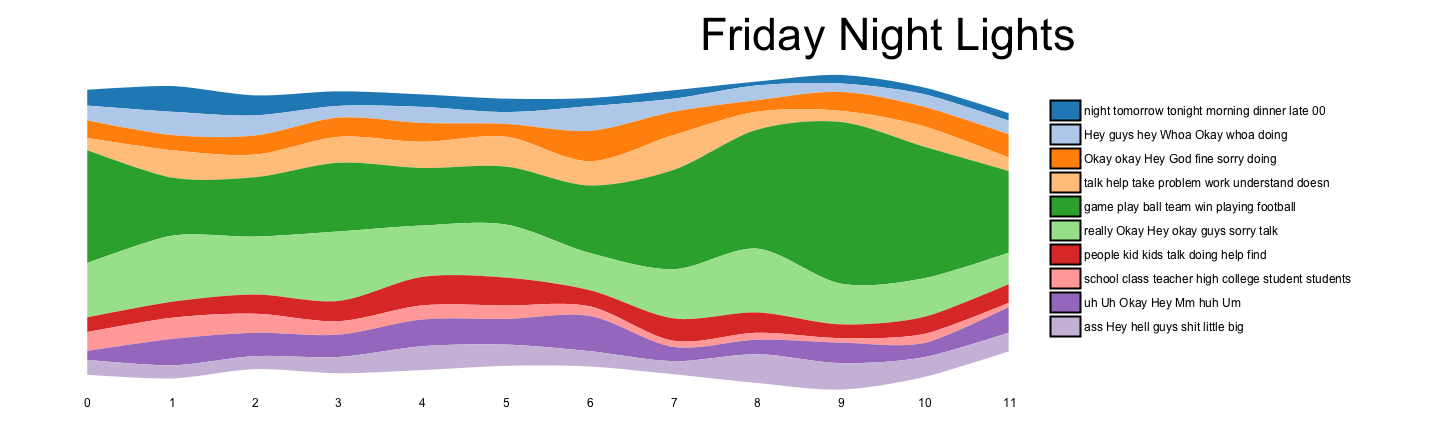

“Friday Night Lights,” on the other, tends to dispose of its football materials either in the first scene or between minutes 40-55. Topics around school and conversation seem to be more concentrated between minutes 10 to 40. Part of this is probably the first-season trend towards ending the episode with the game of the week. The show’s perpetual near-cancellation was always tied to the way audiences couldn’t tell if it was a football show or a family drama; the way that tension is mirrored in episodic structure is interesting.

Cop/lawyer shows often have the strongest signatures. Perry Mason, like Law & Order, doesn’t get into the courtroom for quite a while: but unlike the more recent show, it also takes its time in getting to the murder (which usually isn’t mentioned until almost a quarter of the way in.

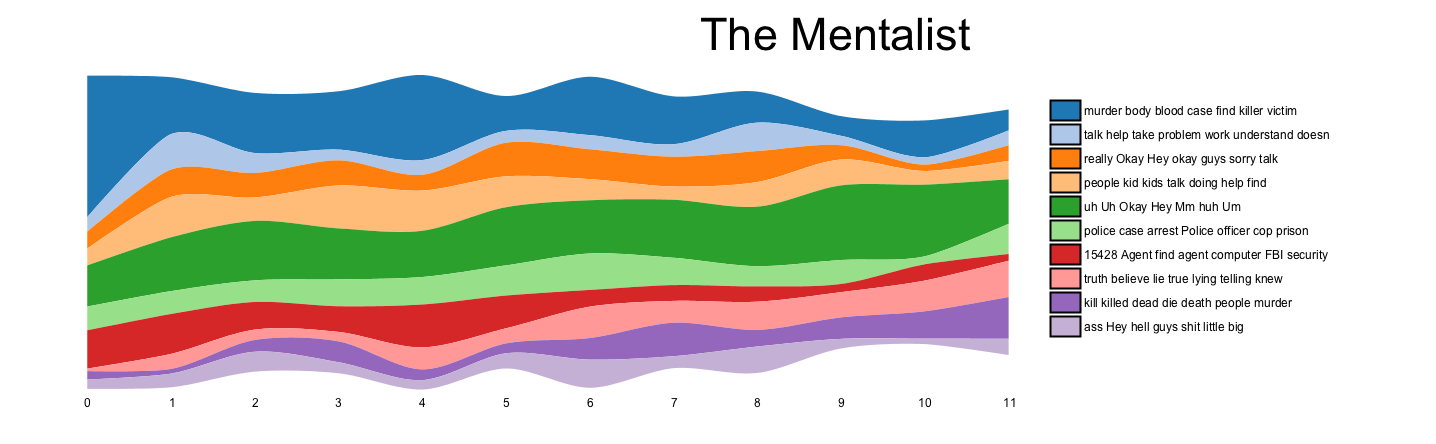

“The Mentalist” moves from actually talking about the murder not into a court case, but into topics about truth and lying, and talking about “killing” and “death” (as distinguished, interestingly, from “murder” and “body”). But above all, the last half is concerned with mumbling: the topic dominated by “uh”, “Uh,” and “Okay” comes to dominate.

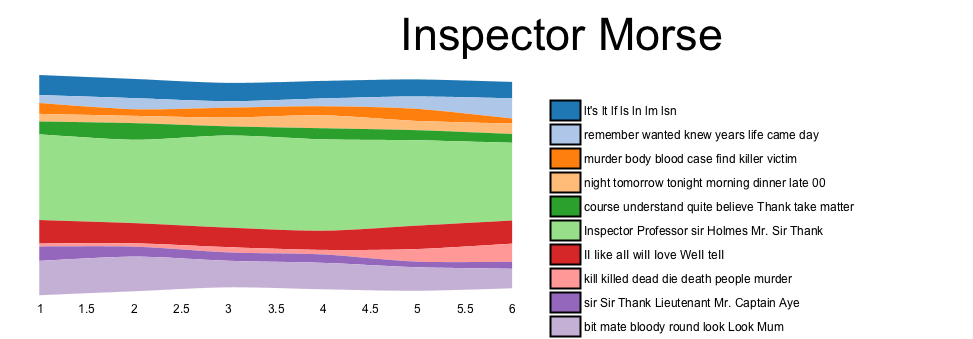

British mysteries have their own topical signature; neither cops nor lawyers, but “Inspector Professor sir Holmes.” “Poirot” is typical; more about the detectives as the show proceeds, less of the upper-class “dear little course darling” chit-chat, and very little talk about how the murder actually happened until the last quarter of the episode.

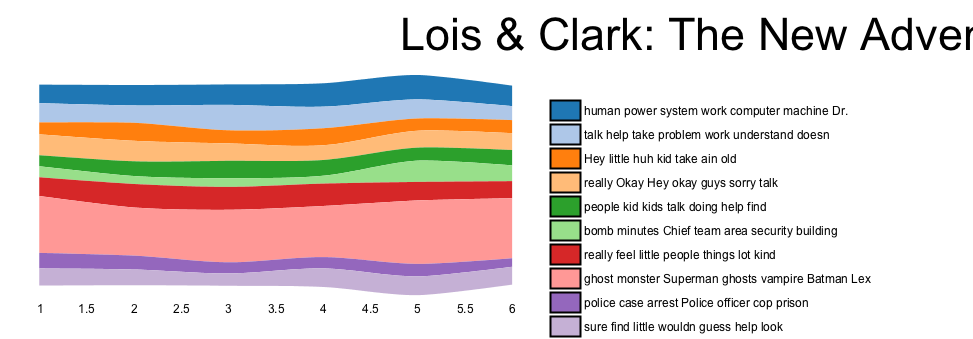

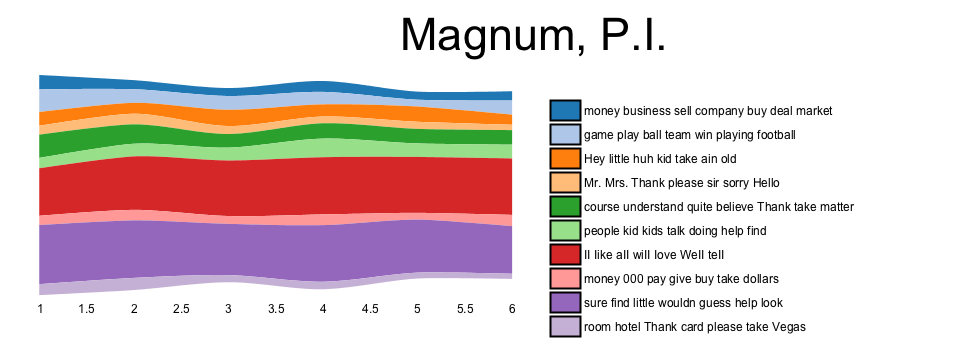

Other types of dramas show fewer structural signatures, at least in their most common topics.

“The West Wing,” slightly decreases the amount of time it spends talking about the presidency (at least until the last scene), and talks a bit more about “talking, helping, problems.” But the signal is overall quite weak.

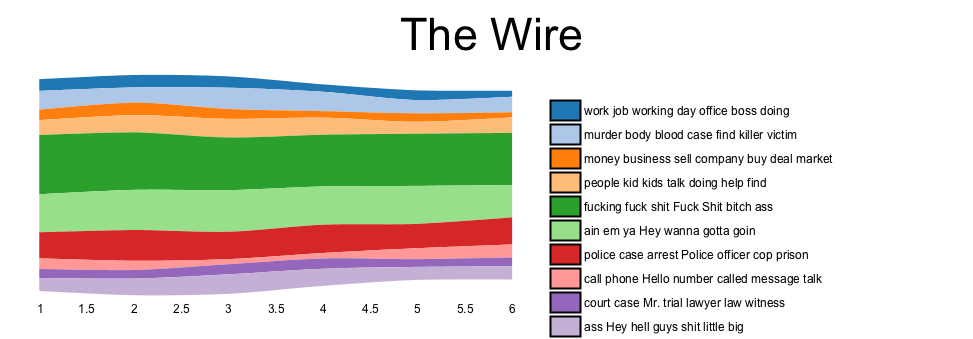

“The Wire” is distinguished by its slang and curses above all; and there’s no strong sign of temporality in how they’re used.

Comedies are less easily read in this version for two reasons. The first is that their topics seem to frequently be more conversational. (A better list of stop words might fix this). For example, “The Office” does have a business topic that generally prevails: but most of the major topics are pure filler.

More problematic is the way that I’ve chunked up the shows; first into 3 minute chunks, and then into twelfth of the show. This helps to keep the total number of documents down. But for twenty-minute shows, it also means that the vagaries of rounding will make certain twelfths very rare, and the charts far too bumpy. The chart for “The Simpsons” is mostly destroyed by this: only a couple episodes seem to have a chunk four out of twelve, so outer space and hospitals seem far more important to the show than they really are.

If I break it into 6 sections rather than 12, “The Simpsons” has a much clearer arc: mostly stable, with a decrease in most types of dialogue but particularly (as I noted before) in the language about “school”, and an increase in the weighty topic “life death world fear heart God soul,” something that’s a little surprising to see in an animated comedy.

For this reason, in the appendix below I’m showing shows divided in sixths rather than twelfths.

And just to repeat at the end: Part II of this series, which goes into quantifying the fundamental shared elements of plot arcs, is now up here.

Here are 150 other shows. Let me know if there’s an obvious show missing.

A Touch of Frost

Agatha Christie’s Poirot

Alfred Hitchcock Presents

Alias

Ally McBeal

American Dad!

Andromeda

Angel

Army Wives

As Time Goes By

Babylon 5

Battlestar Galactica

Beverly Hills, 90210

Bewitched

Big Love

Bones

Boston Legal

Brothers %26 Sisters

Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Burn Notice

Charmed

Cheers

Chuck

Cold Case

Columbo

Crossing Jordan

CSI- Crime Scene Investigation

CSI- Miami

CSI- NY

Curb Your Enthusiasm

Dallas

Desperate Housewives

Dexter

Doctor Who

Due South

Earth- Final Conflict

Enterprise

Entourage

ER

Eureka

Everwood

Everybody Loves Raymond

Family Guy

Farscape

Felicity

Forever Knight

Foyle’s War

Frasier

Friday Night Lights

Friends

Fringe

Get Smart

Ghost Whisperer

Gossip Girl

Greek

Grey’s Anatomy

Hercules- The Legendary Journeys

Highlander

Hogan’s Heroes

Home Improvement

House M.D.

How I Met Your Mother

Hustle

In Treatment

Inspector Morse

JAG

Joan of Arcadia

Justice League

Knight Rider

Kung Fu

Kyle XY

La Femme Nikita

Las Vegas

Law %26 Order- Criminal Intent

Law %26 Order- Special Victims Unit

Law %26 Order

Legend of the Seeker

Lexx

Lois %26 Clark- The New Adventures of Superman

Lost

MacGyver

Magnum%2C P.I.

Malcolm in the Middle

Married with Children

Medium

Melrose Place

Miami Vice

Midsomer Murders

Mission- Impossible

Monk

Murder%2C She Wrote

My Name Is Earl

NCIS- Naval Criminal Investigative Service

Nip-Tuck

Northern Exposure

Numb3rs

NYPD Blue

One Tree Hill

Only Fools and Horses….

Oz

Perry Mason

Prison Break

Private Practice

Psych

ReGenesis

Relic Hunter

Remington Steele

Rescue Me

Roswell

Rumpole of the Bailey

Scrubs

SeaQuest DSV

Seinfeld

Sex and the City

Six Feet Under

Sliders

Smallville

South Park

Spin City

Star Trek- Voyager

Star Trek

Stargate- Atlantis

Stargate SG-1

Supernatural

Survivor

Tales from the Crypt

That ’70s Show

The 4400

The A-Team

The Closer

The Dead Zone

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air

The Guardian

The Invaders

The King of Queens

The L Word

The Lost World

The O.C.

The Office

The Pretender

The Shield

The Simpsons

The Sopranos

The Twilight Zone

The Universe

The West Wing

The Wire

The X Files

True Blood

Two and a Half Men

Ugly Betty

Veronica Mars

Waking the Dead

Will %26 Grace

Without a Trace

Wonder Woman

.png)

Comments:

This looks really innovative and really valuable; …

Ted Underwood - Dec 4, 2014

This looks really innovative and really valuable; I’m sure it’s a method other people will want to use.

Have you tried generating models that are specific to a single show? It might not help; corpus size might be too small. On the other hand, it might reveal variation and temporal patterning within shows that currently look quite constant across time.

Single-show topics would probably work. For this v…

Ben - Dec 4, 2014

Single-show topics would probably work. For this version, I’m sticking with the current Bookworm-Mallet interface, which is one topic model per corpus. But that might be worth changing. I built a model on the Simpsons with each text as a line of dialogue; that produced junk, but probably because the text size was too small. I suspect a single-show, three-minute-chunk model on something richer, like “The Wire,” would reveal some more useful topics. (Although I just don’t think there’s much quantifiable about the structure of “Wire” episodes, though I might be wrong.)

One thing not noted here is that across the whole corpus–movies and everything–temporal signatures are quite strong.

Probably I’ve got to write another post, too, about the difference between screen time and historical time. Topic modeling has fewer problems, I think, in this domain; but there are some big ones around repeated phrases. (“To Boldly Go Where No (Man|One) has gone before”, repeated a few hundred times, is for sure pushing the model in a particular direction.)

This is very interesting! I would be curious to se…

Unknown - Dec 4, 2014

This is very interesting! I would be curious to see a topic model of “Community” because of its “meta” nature and frequent parody. Would its “Law and Order” episode fit a pattern more like Law and Order or like other episodes of Community?

Yeah, I’ve wondered about Community.

Ben - Dec 4, 2014

Yeah, I’ve wondered about Community. Here’s the overall arc for it: a move away from the school, and towards sex in the middle.

What’s particularly interesting there is that we know Dan Harmon is actually writing every episode according to an 8-part pre-defined schematic. Which means there should be some way to track the movement around his “Story Circle,” or some other Campbellian myth-archetype.

Awesome. So many interesting questions here. One o…

Ted Underwood - Dec 4, 2014

Awesome. So many interesting questions here. One of the things you’re hinting above is that it would be possible to do this visualization also just for a generic narrative arc, and there could be lots of interesting details revealed there. Just eyeballing above, it seems that certain topics (“sorry,” “remember,” etc) are so to speak Act III topics. But then, maybe those patterns also change from decade to decade … so many interesting questions!

I’ve noticed the problem of repeated phrases when topic modeling books as well. I’ve gone to a lot of trouble to address the ‘ running headers ’ at the tops of pages, because that repetition can otherwise become a significant kind of noise.

But these are all minor tuning details. It’s a great method.

Nice! I can’t decide if I am surprised or not …

Unknown - Dec 5, 2014

Nice! I can’t decide if I am surprised or not at how dominate conversational artifacts are, given the nature of the show. Perhaps this is another instance when eliminating stop words might lead to some more revealing topics? To echo Ted, these models bring up some very interesting questions. Great work!

Yeah, once I feed the genre information into this …

Ben - Dec 5, 2014

Yeah, once I feed the genre information into this Bookworm instance, I’ll definitely take a stab at the typical arcs for at least TV-comedy, movie-comedy, and movie-drama. (Plus maybe the Bechdel test failures compared to the non-Bechdel test ones.) I’ve looked at the overall arcs, and they’re pretty interesting (and quite strong); “morning tomorrow night day today 00 tonight” is more than twice as strong in the first sixth than in the last one.

These are brilliant, I like the way you represent …

David Sherlock - Jan 3, 2015

These are brilliant, I like the way you represent change in the topics over time. How do you do the diagrams? Are you using ggplot2? Do you have any code examples you would be willing to share?