Some preliminary analysis of the Texas salary-by-major data.

I did a slightly deeper dive into data about the salaries by college majors while working on my new Atlantic article on the humanities crisis. As I say there, the quality of data about salaries by college major has improved dramatically in the last 8 years. I linked to others’ analysis of the ACS data rather than run my own, but I did some preliminary exploration of salary stuff that may be useful to see.

That all this salary data exists is, in certain ways, a bad thing–it reflects the ongoing drive to view college majors purely through return on income, without even a halfhearted attempt to make the results valid. (Randomly assign students into college majors and look at their incomes, and we’d be talking; but it’s flabbergasting that anyone thinks that business majors often make more than English majors because their education prepared them to, rather than that the people who major in business, you know, care more about money than English majors do.

Anyway, in addition to the ACS data I worked with there, I also took a look at a newer form of information that’s just coming online now. The University of Texas is pioneering a new system that will report earnings not just by major, but by school. It seems like the census bureau and the NCES may expand this kind of system of other schools.

This begins to solve, on the surface, a major problem with earnings statistics, which is that majors aren’t offered at the same spectrum of institutions. Art history majors might actually be doing pretty well on the job market; but that might be because only rich kids at elite schools major in art history. Engineering majors make more money than anyone else; but they also come from wealthier families than anyone else, and may graduate from wealthier schools.

It also creates an enormous new problem that I want to underline before I show the charts, by not taking student characteristics into account. I’ve written before about how completely pernicious major earnings statistics that fail to take gender gaps into account are: since gender is a more important determinant of earnings than college major except in extreme cases, a list of majors by earnings often implicitly ranks majors by how male they are. Philosophy might end up having the highest salaries of any humanities field, say, because it’s entirely dominated by men; but that doesn’t mean male philosophy majors make more than male history majors.

This issue is addressed in the IHE article I link above with reference to race (not sex):

Troutman said one black male student told him he didn’t want to know what he would earn – he wanted to know what his white peer would make. So the idea was scrapped.

Which is a fine point, in certain ways: to release the earnings of white men by college major instead of everyone would be interesting, if obviously crazy. But that it isn’t the data they’re releasing; by mish-mashing demographic characteristics, they create crazy incentive structures. If departments at state schools are going to be targeted for contraction based on their income numbers, there is now a clear route to preserving them: discriminate against women to force them out of your major, since they’re more likely to experience pay discrimination, leave the workforce, work part time, or accept lower-paying jobs with more flexibility.

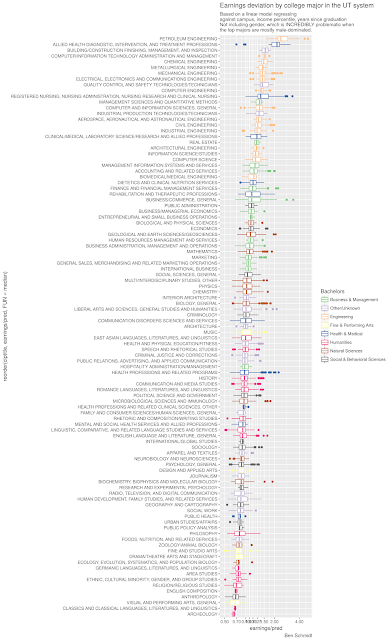

Having said that, the data is interesting and more fine grained than other salary data. To explore it, I look not at the actual earnings, but at the earnings deviation for each batch of students based on a linear model. For example: graduates of UT-Austin typically make about $10,000 more than graduates of UT-El Paso; graduates ten years out typically make 25,000 more than graduates one year out. So if you’re comparing the salaries of ten-year-out Austin sociologists to one-year-out El Paso engineers, you should start with the baseline that the sociologists will make $35,000 more. If it’s less, that’s a point in the engineers’ favor; if it’s more, score one for sociology.

The following chart shows every major in the UT system by its deviation. A score of 1 means majors make more than you’d expect; a score of 2 means twice as much. The boxplot indicates the range of results for cohorts: one point is (eg.) the 25th-percentile income for UT-Brownsville economics majors of the class of 2003 five years out. Interpretation below.

Engineers are doing extremely well. This is probably good, because we need the job market for engineers to be artificially restricted; much like doctors, a bad engineer can kill you, and so we can’t have mediocre professionals wandering around. Median income doesn’t answer one interesting question; what happens to people with engineering degrees who don’t become accredited engineers. (I really know very little about the engineering profession.)

Certain features appear Texas-specific. Becoming a petroleum engineer in Texas in the early 2000s is a good idea; it also may be a ship that has sailed. Geology majors’ high incomes are probably related to the oil industry.

Business majors look better on this chart than on some other earnings indicators I’ve seen: often marketing (say) looks like a poor career choice.

Economics has a high set of incomes: but other than that, there isn’t much of a difference between humanities and social sciences. The highest-income humanists seem to come from history and English–these are also the fields that have seen the biggest drops. East Asian studies is also doing quite well.

STEM is not a block, and we should not be talking about “STEM majors” as if they all do equally well. Biology-affiliated fields, especially other than general biology, all do quite poorly. (By the way: it’s actually not that common for bio majors to go to med school. Out of 150,000 bio majors, 10,000 go to med school each year). Zoology and ecology have earnings comparable to the lowest-paid majors overall. If you lump *any* major in with the engineers, they’ll collectively have high incomes; but so what?

The error bars here are fairly wide for majors offered at multiple schools. History probably does make more than psychology; but the range on both is wide. Some philosophy cohorts make more than the average. Etc.

Connection between income and change in major numbers.

One other chart is possible with this data that answers a lot of questions I’ve had; what’s the relationship between the earnings multiplier and the change in major numbers? In other words, are students actually deserting the humanities?

Comments:

One possibility: there’s not a close relations…

ross - Aug 3, 2018

One possibility: there’s not a close relationship between earnings multiplier and enrollment change, because most people have not had the data to really make that call (until now). Humanities has the reputation for being low paying, whereas STEM fields which do not pay well do not (people think all STEM pays well). If this is the case, then the fact that more data is coming out may cause that relation to tighten up more in the future.

By the way, while it is unquestionably true that women suffer from pay discrimination, another factor is that there is a measurable and real difference in how much the median woman weighs pay in her career (and major) decisions, compared to men. In fact these may be related; women are offered lower pay, even by women bosses in some cases, because of a tendency to think that they will accept it and not bolt. If student loan debt causes women to prioritize pay more, and be more willing to change jobs in search of a higher salary, the differential might shrink, not only because of that fact alone but also because it may cause employers to be less confident that they can pay less to women and still keep them as employees.

By the way, I have two engineering degrees, and I have never gotten any kind of engineering certification. That is not unusual. Engineering degrees are, in many cases, enough in themselves to signal to an employer that you can do technical work. There are some fields like civil engineering where certification is much more important, but in most engineering fields it is not.

That’s useful information about engineering, t…

Ben - Sep 2, 2018

That’s useful information about engineering, thanks. I’m very curious how the skills-vs-signaling distinction pays out in the hiring of engineering students. There’s also the possibility that engineering schools nonetheless weed out more heavily than most other programs.

I think you’re right that this is one of the cases where the existence of data may change the way the data works going forward. That would suggest that higher ed might be even more upended in the next decade.

One problematic possibility is if, say, certain degrees (say, engineering) continue to be able to weed out the worst candidate majors, while others (say, psychology) have to let everyone in. Then wage gaps might persist or even accelerate (as everyone tries to major in engineering) out of proportion to the actual value added.

Importance attributed to pay is important, yes. And there are certainly gender correlations. There may also be major correlations, too–I suspect part of the problem is that, even now, people who major in humanities are those who attribute less importance to being wealthy. There could even be causal effects, which would really skunk up quantitative analysis.