Some notes on corpora for diachronic word2vec

I want to post a quick methodological note on diachronic (and other forms of comparative) word2vec models.

This is a really interesting field right now. Hamilton et al have a nice paper that shows how to track changes using procrustean transformations: as the grad students in my DH class will tell you with some dismay, the web site is all humanists really need to get the gist.

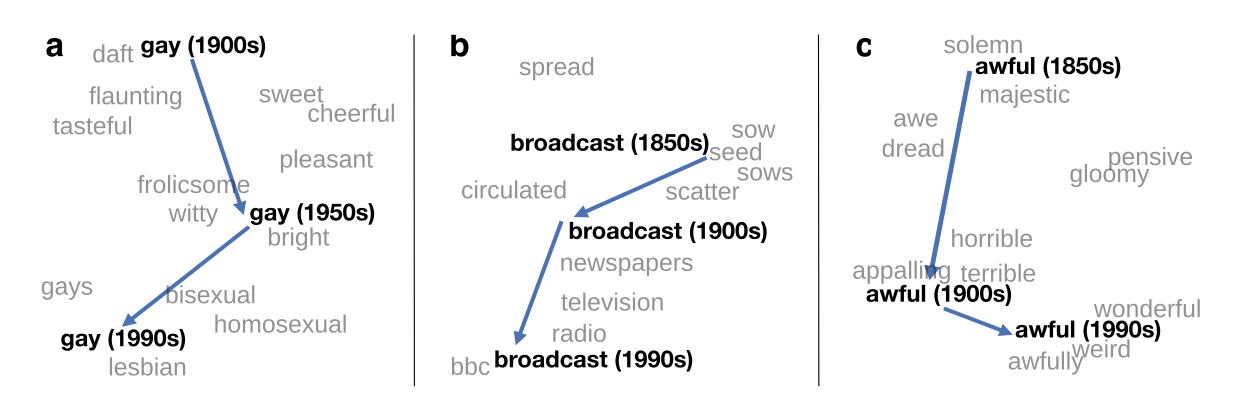

Semantic shifts from Hamilton, Leskovec, and Jurafsky

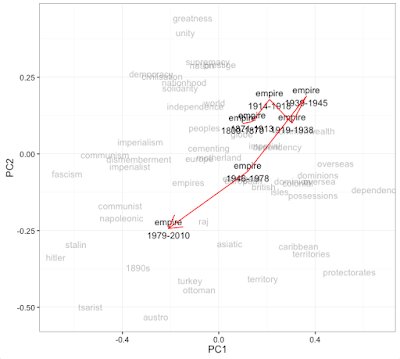

I think these plots are really fascinating and potentially useful for researchers. Just like Google Ngrams lets you see how a word changed in frequency, these let you see how a word changed in *context*. That can be useful in all the ways that Ngrams is, without necessarily needing a quantitative, operationalized research question. I’m working on building this into my R package for building and exploring word2vec models: here, for example, is a visualization of how the use of the word “empire” changes across five time chunks in the words spoken on the floor of the British parliament (i.e., the Hansard Corpus). This seems to me to be a potentially interesting way of exploring a large corpus like this.

I would gloss this to say that “empire” remains in a relatively similar semantic space until 1945, although it drifts from a space of national “greatness”, “unity”, and “solidarity” towards a more technical language of “dependencies” and “possessions.” But then after 1945 the parliamentarians tend to forget that they ever had an empire at all; in the post-Thatcher period, the British speak of “empire” in the same breath as “Stalinism,” “Napoleonic” adventures, and the “Asiatic” empires of the past.

This visualization suggests these observations but in no way proves it; at the least, you’d have to look at the individual relationships in each decade to understand how the PCA is parcelling things out, and if you were to write a paper on British uses of empire you might want to retreat to more traditional concordance methods. But the ability to perform these kinds of explorations in sub-second times for any word is really exciting to me; given an appropriate master corpus, this would be an extremely interesting web tool to build into a large-scale discovery engine.

But “given an appropriate master corpus” is a big caveat. The Hansard corpus is a decent one, which is why I use it here. My least favorite thing about the Stanford paper is that they use the Google Ngrams 5-grams as the basis for their diachronic comparisons.

Now I see there’s a new paper out by Johannes Hellrich and Udo Hahn called “Bad Company—Neighborhoods in Neural Embedding Spaces Considered Harmful” that follows in their footsteps by suggesting that SGNS word2vec shouldn’t be used because the random seeding produces unreliably different neighborhoods for words. This is a useful concern to raise; I like to try to treat SGNS word2vec as essentially a low-memory matrix factorization algorithm, but they suggest it varies significantly between runs. We certainly need more studies along these lines.

But they, too, use the Google Ngrams 5-grams for this, which makes it very hard to tell the difference between problems of the training corpus and problems of the word2vec algorithm. This is partly because of the well-known issues with the selection criteria, compounded by their decision to use a time periods (2005-2009) which the authors of Google Ngrams highly discourage including in published study. But it’s even more because of the weird differences between Google Ngrams 5grams and actual 5-character sequences of natural language text. Ngrams only includes phrases that appear more than 40 times; that means that the vast majority of the text of books is thrown out in favor of pat or frequent phrases. Going by Hellrich and Hahn’s counts, in the English Fiction corpus, three in four five-word phrases are thrown away.

I’ve never seen a good summary of what’s lost, but I can say with certainty that the effects are much worse for infrequent words than for frequent words. I don’t have a well-indexed copy of the five grams, but some random spot checks on three grams shows that infrequent words like “preexistent” or “inebriated” (in bin 5 below) are dropped 85% of the time in the 3grams, while moderately common words like “greed” or “upstairs” are dropped more like 60% of the time. Super common words are presumably dropped even less, and I imagine the numbers rise and the gaps widen somewhat as you approach 5-grams.

So for a word like “lazzaroni,” which the authors worry shouldn’t be showing up in the near neighborhood of “romantic,” the training data is learning on the basis of a very small number of pat phrases; the thirdfifth-most common 3-gram starting with “Lazzaroni” in ngrams comes from a widely reprinted passage of George Eliot’s Adam Bede, “Neither are picturesque lazzaroni or romantic criminals half so frequent as your common labourer.”

In natural language, there would be a wide array of less pat phrases the word2vec algorithm would encounter with a word like that; in the ngrams five-grams, though, I doubt it ever sees Lazzaroni outside more than five or ten phrases. What will the result of this be? I’m not entirely sure, but I doubt it’s good. Uncommon words will be boxed into the contexts they are used in by one or a few widely-reprinted authors or pat phrases, rather than how they were used at large; and then those contexts will, at scale, potentially shift around the locations of somewhat common words in confusing ways because the signals tying them together are so strong. This applies regardless of whether the algorithm is word2vec, or PPMI-SVD, as the authors suggest.

So while I’d really like to know how word2vec reliability performs *and* I’d like to see it or whatever else (SVD-PPMI, yeah; I don’t know how they handle some computational complexity issues around that, and I’d like to hear more) extended to work with diachronic historical corpora, the next step is clearly to stop doing this with Google Ngrams and finding actual natural language to work with.