Population Density 1: Do cities have a land area? And a literal use of the Joy Division map

I’ve been doing a lot of reading about population density cartography recently. With election-map cartography remaining a major issue, there’s been lots of discussion of them: and the “Joy Plot” is currently getting lots of attention.

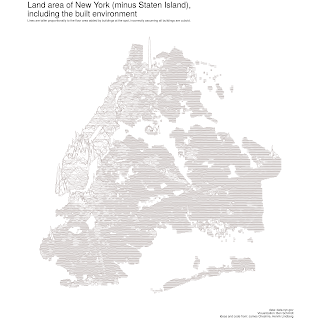

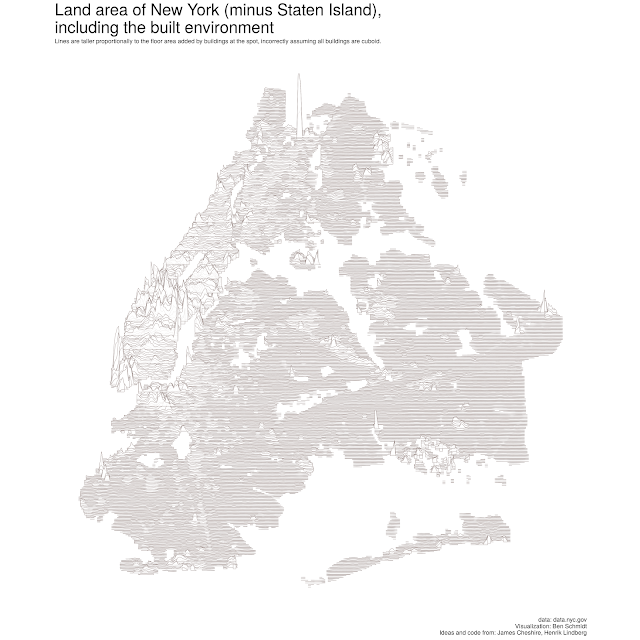

So I thought I’d finally post some musings I wrote up last month about population density, the built environment, and this plot I made of New York City building height:

This chart appears at the bottom of this post, but bigger!

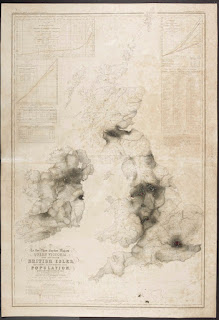

One of the continuing strands is that cities have always present major challenges for population density mapping. The idea of population density, at heart, imagines humans as particles that repel each other on a surface; the intense aggregation of populations in a few cities are unnatural. Walker’s maps of population density (1870) in the American west exclude cities with populations over 2500; August Petermann’s maps of the British population for the 1851 census do the same. (Here’s one of Petermann’s).

So: cities are unnatural and don’t really count when mapping ordinary human population density. I just encountered the most extreme enunciation of this problem in a book by Cornell professor Francis Willcox from 1897, Density and Distribution of Population in the United States at the Eleventh Census.

Density of population may be defined as the average number of human beings living on a unit of land surface. […] Rough volumetric measurements, such as the number of persons to a dwelling or a room, or the cubic feet of air per capita, are sometimes used in congested districts and notwithstanding the obvious objections to so vague a unit as a dwelling or room, they may give better results than the method in general use. For with modern advances in engineering, civilized people have become able to live or work at some distance above or below the surface, where the advantages of mines or cities assemble them. Under such circumstances the ratio of population to surface may be insignificant or misleading. [My emphasis]

So not only do cities present unnatural density; the widespread practice of building above or below ground means that there should be some other criteria of measuring density. Land area isn’t constant but manipulable; build a two-story warehouse or dig a tunnel, and you’ve doubled the space for people to live in.

There are some interesting technical questions here. It got me wondering about a distorted cartogram that might distend areas not by population, but simply by surface area. Does it really make a difference?

To check, I downloaded a list of building footprints from nyc.gov and just ran some numbers on how many square feet of floor space. I assumed all buildings in the city had the same shape at the top floor as at the ground, which is spectacularly wrong–after the 1916 zoning code, most tall buildings were supposed to imitate the tiered floorplan of the Woolworth building–so this should be taken as an upper limit, not a description of fact. But the building stock in the city is old enough that I doubt it’s an egregious overestimate: I’d guess, wildly, that this overstates floor space by five to thirty percent. (Even with this assumption, half of all floor space in the city is in buildings of five or fewer floors; I also assume that no buildings have basements, when in fact most do.)

So: how much building space is there in NYC? By my calculation, the answer comes out to about 225 square miles of indoor space; that’s less than the land area of the city (300 sq mi). Which is to say: if you could tear up every piece of linoleum, concrete, and parquet from every floor above the first in Manhattan, you’d be able to lay each one on the ground on unbuilt space in the city’s streets, parks, airports, and parking lots.

Subtract out first floors, and the built environment adds at most 164 square miles to the cities area, bumping it from 300 to 460 square miles. That’s a lot in urban terms–construction has added to the surface of the city about the combined area of Brooklyn and Queens–but it’s not an amount that would make any difference, in, say, a map of the national popular vote by area. So: even a century of development later, Willcox’s critique doesn’t argue for rethinking the denominator in population density.

Still, it suggests a kind of neat way of thinking about walking across the city. Suppose you were to start at the Hudson and walk due east across the city. Every time you encounter a multistory building, you walk over each floor exactly once. How much out of your way do you go?

This suggests a kind of interesting alteration of the “Joy Division” maps that have been popular since (at least) James Cheshire’s great map of population by latitude. Those charts essentially do a double encoding scheme on the y axis: it means variation but also population. That’s clever, but population height means nothing in the context of latitude and longitude.

Plotting extra land area instead of population adds the interesting additional constraint that there’s an obvious connection between the primary scaling factor (latitude) and the secondary one (additional area). The additional distance in the latitude factor is on the same scale as the rest of the map.

It doesn’t quite match the constraint that distance matches onto the length of travel you would go if walking across the city at that line; for that to be true, the heights should be cut in half, and there would need to be histogram bars so that at each point you climb up and then down again. (Or you could do it as a vibrating squiggle, setting both amplitude and frequency to get the line the right length–I’m curious enough about that one that I might run it.)