OCR failures in 2016

This is a quick digital-humanities public service post with a few sketchy questions about OCR as performed by Google.

When I started working intentionally with computational texts in 2010 or so, I spent a while worrying about the various ways that OCR–optical character recognition–could fail.

But a lot of that knowledge seems to have become out of date with the switch to whatever post-ABBY, post-Tesseract state of the art has emerged.

I used to think of OCR mistakes taking place inside of the standard ASCII character set, like this image from Ted Underwood I’ve used occasionally in slide decks for the past few years:

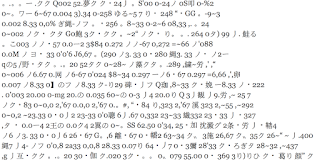

But as I browse through the Google-executed OCR, I’m seeing an increasing number of character-set issues that are more like this, handwritten numbers into a mix of numbers and Chinese characters.

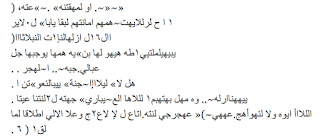

or this set of typewriting into Arabic:

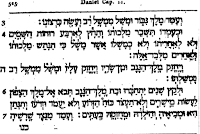

or this Hebrew into Arabic:

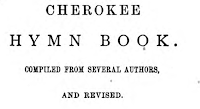

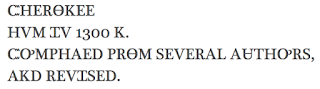

Or this set of English into Cherokee characters:

That last example is the key to what’s going on here: the book itself *is* mostly in Cherokee, but the title page is not. Nonetheless, Google OCR translates the whole thing as being in Cherokee, making some terrible suppositions along the way: depending on your font set, you may not be able to display the following publisher information.

ᏢᎻᏆᏞᎪᎠᎬᏞᏢᎻᏆᎪ:ᎪᎷᎬᎡᏆᏨᎪᎡ ᏴᎪᏢᎢᏆᏚᎢ ᏢᏌᏴᏞᏆᏟᎪᎢᏆᏫᏒ ᏚᏫᏩᏦᎬᎢᎩ,1420 ᏨᎻᎬᏚᎢᎡᏴᎢ ᏚᎢᎡᎬᎬᎢ

Some unstructured takeaways:

I usually think of OCR as happening on a letter-by-letter basis with some pre-trained sense of the underlying dictionary. But the state-of-the-art is working at a much larger level where it makes inference on the basis of full pages and books, so the fact that a lot of a book is sideways can make the pages that *aren’t* sideways get read as Arabic.

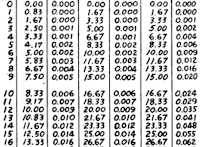

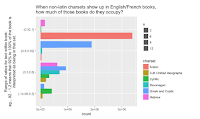

There’s a cultural imperialism at work here. The Google algorithms can succesfully recognize a book as Cherokee, but nonetheless only about 3 in 4 books in Arabic, Chinese, Greek, or Hebrew are in predominantly the appropriate character set. (Image). This is a little complicated, though; these are pre-1922 texts I’m looking at, so most Japanese, Chinese, and Arabic is not printed.

(This is based on a random sample of 28,075 pre-1922 books from Hathi).

But when you look at what characters are incorrectly imputed onto English and French texts, things get tricky. When books are interpreted as Arabic, the entire book tends to get read in Arabic script; the CJK unified ideograph set tends be interspersed with other languages. And there are some baseline assumptions throughout here about what languages count: the unified Han character set gets read in a lot, as do the Japanese extensions, but the only substantial example of Thai character sets erroneously read I can find is not from English but from Sanskrit. That’s an easy problem to define: Google doesn’t like to recognize Thai script, and that’s bad if you want to read Thai. But why does Google allow books to contain trace amounts of Greek, Cyrillic, and Chinese, but not Arabic or Hebrew? This probably has something to do with training data that includes western-style numerals in particular, I would bet. (You can see this in action above: the Arabic examples I pasted are almost straight Arabic, while the Chinese ones are interspersed.) The implications of this for large corpora are fuzzy to me.

You can read this chart if you like, but it’s probably not clear what it shows.

Ordinary mortals don’t have access to extensive visual data about books, but the decisions about character set that these algorithms make is a potentially useful shadow of overall image info. Sheet music isn’t OCR’ed by Google, for instance, as anything but junk. But it looks to me like it should be possible to train a classifier to pull out sheet music from the Hathi trust just based on a few seeds and the OCR errors that sheet music tends to be misread as.