Lumpy words

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; min-height: 14.0px}

What are the most distinctive words in the nineteenth century? That’s an impossible question, of course. But as I started to say in my first post about bookcounts, [link] we can find something useful–the words that are most concentrated in specific texts. Some words appear at about the same rate in all books, while some are more highly concentrated in particular books. And historically, the words that are more highly concentrated may be more specific in their meanings–at the very least, they might help us to analyze genre or other forms of contextual distribution.

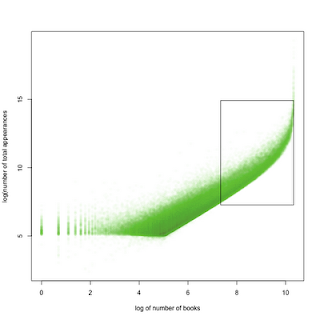

Because of computing power limitations, I can’t use all of my 200,000 words to analyze genre–I need to pick a subset that will do most of the heavy lifting. I’m doing this by finding outliers on the curve of words against books. First, I’ll show you that curve again. This time, I’ve made both axes logarithmic, which makes it easier to fit a curve. And the box shows the subset I’m going to zoom in on for classification–dropping a) the hundred most common words, and b) any words that appear in less than 5% of all books. The first are too common to be of great use (and confuse my curve fitting), and the second are so rare I’d need too many of them to make for useful categorization.

(more after the break)

OK, so that’s what we’ve had so far. Now let’s look at that chunk. I’m going to use loess to fit a line to it, and select the words that are the greatest outliers from that line. Red shows words who are distributed across fewer books—more lumpily—than we’d expect, and blue shows words that are distributed more smoothly than we’d expect.

Just at you’d think, there’s a lot more variation on the side of lumpiness than of smoothness. We’re only going to look at the lumpy words from now. Let’s zoom in further so we can see the individual words.

Not bad. It’s a good sign when words as closely related as ‘ plaintiff ’ and ‘ defendant ’ appear right next to each other. You can also books using archaic pronouns, latin, religious language, and a variety of scientific and medical terms. Plus some colloquialisms–any work with a lot of “ain’ts” is probably a popular novel, though the reverse isn’t true “you” and “dont” fall into this category as well.

What are the top 20 lumpily-distributed words, you ask?

plaintiff defendant defendants urine bie mucous testator acid membrane

3.778093 3.467491 3.362822 3.172946 2.852449 2.840315 2.659488 2.630043 2.607742

adv abdominal fig tov glands diagnosis que bladder kidney

2.537471 2.482434 2.457205 2.442361 2.432046 2.426817 2.379019 2.360535 2.320224

quae statute

2.266063 2.262361

This raises two points:

Fig? What’s special about figs?

There’s way too much medical stuff in here. If this method will help find words than can be useful in classifying, it’s going to require a better way to see which words are different _from each other_, not just from the bulk of words in the language. If we could just load all the words in at once, that would be easy. But as it is now, it’s going to be tricky–we might want to, say, take the 250 most lumpily distributed words, and then take the 50 of those that seem to sort on the most different axes If the database gets running, it could probably take care of itself running on the computer overnight.

Comments:

Looking at this again, I realize “fig.” …

Ben - Dec 6, 2010

Looking at this again, I realize “fig.” is a figure in a book with illustrations. I’m embarrassed it took me so long to figure that out.