Genders and Genres: tracking pronouns

Now back to some texts for a bit. Last spring, I posted a few times about the possibilities for reading genders in large collections of books. I didn’t follow up because I have some concerns about just what to do with this sort of pronoun data. But after talking about it to Ryan Cordell’s class at Northeastern last week, I wanted to think a little bit more about the representation of male and female subjects in late-19th century texts. Further spurs were Matt Jockers recently posted the pronoun usage in his corpus of novels; Jeana Jorgensen pointed to recent research by Kathleen Ragan that suggests that editorial and teller effects have a massive effect on the gender of protagonists in folk tales. Bookworm gives a great platform for looking at this sort of question.

Bookworm offers up a gender-tagged corpus with full data about pronoun use; that means cruder but wider-ranging generalizations about how the gender used in books intersected with the gender of authors. Obviously there’s no shortage in the world of crude and wide-ranging generalizations about gender. The idea here is that by situating statements about how authorial gendered interacts with the gender of individuals presented on the page in their social context, we might be able to do something relatively interesting. Taking a few hundred thousand books tagged by the author’s first names against census data (methodology here), we can see how these patterns in novels and folklore hold across other sorts of data. The exact books used for this search are fully transparently available online at Bookworm. Here’s a basic pronoun search to get started with; clicking to read the texts should show you what sort of books I’m using.

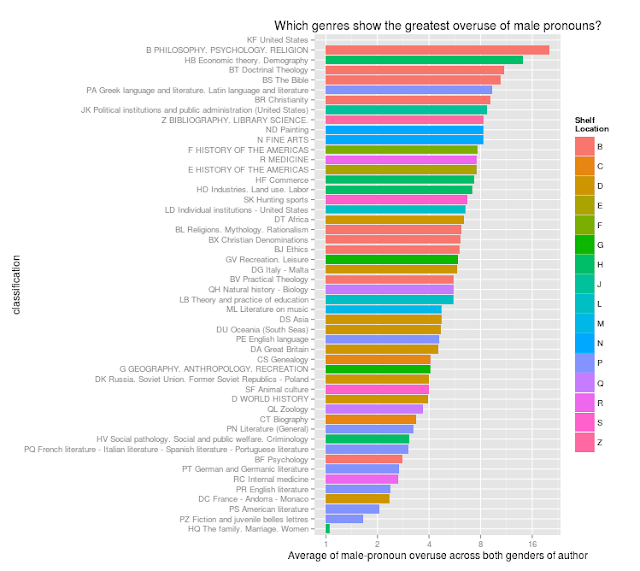

We’re going to be working with ratios here. The raw counts of ‘ him ’ and ‘ her ’ won’t tell much: what we’re interested in is comparative use. The following chart (made with 8 lines of code in R and the forthcoming Bookworm API) shows the top 50 Library of Congress classifications in Bookworm, divided into male- and female-authored books. (Like Jockers, I have an uncategorized bin as well, but I’m not showing that here). The farther to the right, the more the words “he/him/his/himself” are used compared to “she/her/hers/herself.” It’s a log scale: if red and blue are one tick apart that means a twofold difference regardless of how far to the right they are.

This shows that although different fields have different baseline uses of male and female pronouns, there’s also an effect within each shelf location, in which men tend to ‘ overuse ’* male pronouns about 2 to 4 times as much as do women. This is across the largest genres, in books published between 1865 and 1922 in English.

*Overuse is a problematic term, but a convenient one. I’m just pretending it’s self-evident that the ratio of male-to-female pronouns should be 1:1. I can’t say “use” male pronouns because it’s the rate per usage of female pronouns I’m interested in, not the overall rate.

The sizes of the dots show the number of pronouns in the texts I’m checking. There are about 20 million pronouns in PR, English Literature. It’s also worth noting that even among the smallest genres shown, there are still thousands of pronouns: one doesn’t really need a million books to look at this sort of trend. I’m not worrying much about significance for this reason; but keep in mind that for the smaller genres, we might be over-estimating trends significantly.

This is already implicit in the chart above, but it’s interesting to see which fields have the greatest gender gap in their pronouns. The general philosophy-psychology-religion location is the greatest offender, followed by a number of theological* and literature fields: the most female pronouns show up in literature, in the social sciences specifically devoted to ‘ marriage and the family, ’ and in medicine.

*This is the place to mention I’m case-insensitive, so all those Himselfs count as men.

A related question is the size of the gender gap. (Click this chart to enlarge it). Although classical literature has far more male than female pronouns, for example, the difference between male and female authors is trivial. One thing a chart like this tells us is where there may be particularly gendered enclaves. Individual educational institutions (LD) shows a 16-time gap between male and female authors: women use more female pronouns than male pronouns, while men use more than ten times as many male pronouns. This is because, presumably, of gender-segregated schooling, which frequently penetrated all the way to the owners of the schools.

We’re working with ratios of ratios of ratios at this point, so things may get a bit cloudy. But the two previous charts have given us two different models of gender bias:

The pronoun gap: how much more often male pronouns appear than female pronouns. (Idiosyncratically, I’m measuring this as the average of male and female author groups, rather than using the overall average which would be much closer to the average of male authors.)

The pronoun gender gap: How much the pronoun gap for male authors differs from the pronoun gap for female authors. We can add to that a third, which I looked at last year:

The authorship gap: the percentage of authors in the field who are female.

While these are related, they capture really different aspects of the gendered aspects of consumption and production. Treating each genre as—effectively—a single text, we have enough different data points to ask what the relations among these three different types of gender bias are.

The correlation matrix among them looks like this (using rank-ordering so as not to worry about logarithmic vs linear distributions):

\> round(cor(f,method='spearman'),2)

AuthorshipGap PronounGenderGap PronounGap

AuthorshipGap 1.00 0.18 0.60

PronounGenderGap 0.18 1.00 0.31

PronounGap 0.60 0.31 1.00

There’s a strong relationship (r=.6) between author genders and the pronoun gap:

. It’s interesting that the Pronoun Gender Gap falls the furthest from the other two, because in some ways it lies between them: the authorship gap is purely* a function of metadata, while the pronoun gap is purely a function of data. That the gender gap, which is about their interrelation, has nothing else to add suggests that the gender dynamic of internal gaps within a field is completely distinct from the one about access to and presentation in the press. (In a linear model, pronounGenderGap contributes absolutely nothing above PronounGap towards predicting AuthorshipGap: an absurdly high p=.96, where p<0 .05=“” be=”” significant.=“” would=”“>

*Not actually purely: the author’s name is actually part of the textual content in complicated ways I’m ignoring. For example, the “male” author named “George Eliot” on the title page is, in some way, part of the generic convention of reading a more ironic take on the country novel, or something like that.

What’s that mean?

If women had to write “more male” to get into the genres that were dominated by men, there would be a correlation here. So this suggests—in a very sketchy way—that while there are lots of women writing in fiction, fiction is not necessarily a place where women operated under any different constraints than in psychology. That could have all sorts of different implications (maybe female writers were always performing the role of ‘ female writers ’ whatever genre they were in; maybe there were no constraints on women at all, and women ‘ naturally ’ write 100% more male; maybe the constraints on male writers are proportional to the constraints on female writers.) But it does suggest that while on the surface the genders presented in—say—economics and literature don’t have much to do with each other, there may be ways to uncover similarities.

That suggests further we might want to look harder for the areas where women do seem to act differently. I looked at publishers last time: that’s one obvious place. If some publishers seem to be taking women who write with the genre distribution of men, that would be potentially interesting. The statistics on all this will get pretty hairy, but it’s not hard to come up with some interesting questions about the books we’ve inherited and why.

For example: I tend to think digital humanists pay way too little attention to library acquisition patterns. So are there gender patterns affecting libraries? I recently pulled all the originating library data for the books in Bookworm from the Internet Archive: just re-using the code for the first chart, we can see how library collections are biased by gender differently.

Obviously this is heavily inflected by genre. (Less obviously, the genre patterns may be heavily inflected by the underlying libraries.) But not everything can be explained from genre alone: why, for example, does the Methodist BU theological library show a less extreme split than the Presbyterian Princeton Theological Seminary library? Are there sustained differences we could identify in public versus university libraries? And even if the gender patterns reduce to genre, does that tell us how different sorts of institutions responded to—say—the chance to acquire a book by a female economist?

Comments:

That library graph is interesting! There’s a s…

Ted Underwood - Feb 1, 2013

That library graph is interesting! There’s a surprisingly big difference between the means. It seems to me that it might actually be worth doing a regression analysis to figure out whether there’s a “library effect” separate from the “subject category effect” and/or “date-of-publication effect.”

This is a semantic point, but I would tend to describe these call-number groupings as “subject categories” rather than “genres.” It’s semantic partly because we don’t have a firm definition of genre. But, loosely, I think people tend to identify genre with a rhetorical situation and/or form rather than topic. E.g., it would be possible to write a series of personal essays or letters about the “Theory and Practice of Education.” Once collected, they would be in the same subject category as LB books originally composed as monographs – but not necessarily in the same ‘ genre. ’ That distinction probably doesn’t matter a whole lot outside the P call numbers – so I understand why it’s not a big deal for historians. But within the P call numbers the difference between subject and genre becomes enormously important.

Yeah, Bookworm is really waiting for some serious …

Ben - Feb 1, 2013

Yeah, Bookworm is really waiting for some serious multi-level modeling once I read up on the literature. The big problem with the library data is that it’s the contributor, but we don’t know for sure if it’s in the library or not: particularly for libraries approached later in the Google book scanning project, this will be a huge effect that could only be addressed by linking different books to each other for real.

I hear you on the genre thing, but I’m not sure the vocabulary is well enough developed that it’s anything but a muddle. Off the cuff, I’d say that ‘ genre ’ is created at the intersection of style and subject, and the relative importance of the two is very hard to tell. The result of a lot of what you and Matt Jockers are doing may be to push the ‘ genre ’ line farther towards ‘ style ’ or ‘ tenor ’ or ‘ voice. ’ But certain popular phrases like “genre fiction” are basically defined by subject matter.

“Shelf location” is the perfect word, because it’s agnostic about whether the LC classification divides by subject, prestige, or something else. The difference between PS and PZ, say, is almost purely a ‘ genre ’ difference, as is biography being (sometimes) segregated out from the subject of the person being written about. But the subclasses in the Ds, world history, are definitely “subject” divisions.

Short of starting over, I probably would go just with ‘ subject, ’ but since a ‘ subject heading ’ and ‘ subject classification ’ mean two very different things in the library science world, it gets tiresome to steer arou nomenclaure. (And of course, ‘ fiction ’ and ‘ poetry ’ are components of “subjects” by subject heading).

I should say: on a basic linear model of the ratio…

Ben - Feb 1, 2013

I should say: on a basic linear model of the ratio in terms of author gender, lc classification, and library, every single lc classification clocks in at massively significant (p < 10e-15), while every library but one shows up insignificant. (The one exception is the West Virginia University Libraries, which shows a strong pro-male effect: despite the temptation to pick on West Virginia, I’m willing to bet that’s some sort of overfitting.)

All the above increases my curiosity to learn abou…

attention tracking - Mar 5, 2013

All the above increases my curiosity to learn about how to perfectly design a webpage, where should be placed advertisements, how much content is sufficient, are images really necessary and many more things… Thanks

Such an amazing images! I heard that there will be…

teresa bowen - Apr 3, 2013

Such an amazing images! I heard that there will be a design contest next week and for sure lots of people will be interested to join.

philippines logo design

Excellent Share! An exciting dialogue is well wort…

Unknown - May 4, 2013

Excellent Share! An exciting dialogue is well worth comment. I think you ought to compose much more on this matter, it may well not be considered a taboo issue but typically individuals usually are not enough to speak on this sort of topics.

atv performance parts