First Principals

Let me get ahead of myself a little.

For reasons related to my metadata, I had my computer assemble some data on the frequencies of the most common words (I explain why at the end of the post.) But it raises some exciting possibilities using forms of clustering and principal components analysis (PCA); I can’t resist speculating a little bit about what else it can do to help explore ways different languages intersect. With some charts at the bottom.

The computerized text analysis literature I’ve looked at finds strong connections between issues like authorship or genre and rate of use of fairly common words. Mosteller and Wallace’s seminal paper about classifying the Federalist Papers with disputed authorship, for example, found in 1963 that Hamilton and Madison had different rates of use of words like ‘ while, ’ ‘ whilst, ’ and ‘ upon ’ that made it very likely most of the disputed papers were by Madison. More contemporary work like Michael Witmore’s uses clusters of simple word-types (first-person, motion-words, direct addresses) to reproduce early modern genre distinctions. I don’t have anything so sophisticated as either of these (though at least I have a better computer than Mosteller and Wallace), but I can already use the most common words to start to ferret out some traditional genres.

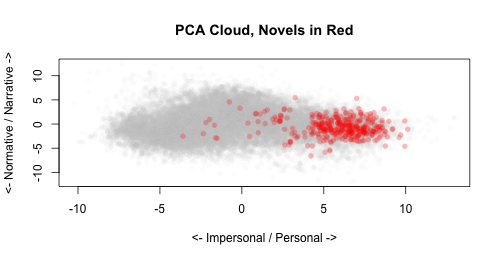

I’m not going to fully explain PCA right now (although even my examples will probably reveal how shaky my understanding is at time). But just to explain these cluster charts show: Some PCA on word frequencies tells me, essentially, how to explain about 17% of the variation among my books using one set of word weights. Some books use the words “she”, “could”, “you”, “he”, and “him” a lot: other books tend to use the words “the”,“which”,“these”,“other”, and “is”. So we could sort the books in our library by their use of those words. And that would correspond to real facts about their genre. You’d probably guess, for example, that the first pile would have a lot more novels, the second book a lot more science.

Now, that’s just one dimension–call it ‘ personal/impersonal, ’ say, although I can’t emphasize enough that that’s a big interpretive leap that might be wrong for all sorts of reasons. PCA gives us lots more dimensions–as many as we feed in words—that let us split our library. The second one, in this case, gives us books that use ‘ the ’, ‘ was ’, ‘ at ’, and “were” on the positive side, and ‘ can ’,’must’, ‘ will ’, and ‘ if ’ on the negative. (Sorry for the programming practice of commas outside the quotes—it’s getting to hard to switch back and forth). Let’s call that one “narrative/normative”, which is even more groundless guess.

So, we’ve got two dimensions. Let’s make a chart where every dot is a book, representing its on both those dimensions. (The width is supposed to reflect the increased discriminatory power of the first factor rather than the second, but most likely I’m not quite getting it right.)

It’s a cloud of unknowing!

This is just one of an infinite number of ways of looking at the data. But PCA tells us it’s an important one, so let’s just see if our preconceived notions of meaning can be mapped on to it. I mentioned novels earlier: what happens if we highlight the books that have “novel” in the title? Having the word novel in the title is neither necessary nor sufficient for being a novel, of course, but it’s a good sign we’ll get titles like this:

> sample(catalogtitle\[grep("novel",catalogtitle)],5)

[1] “The sins of the children : a novel”

“Trilby, a novel”

“The auction block : a novel of New York life”

[4] “In paradise; a novel”

“Charming to her latest day; a novel”

And it works pretty well:

We’d expect novels to have a lot of personal language, but it’s sort of funny that they would trail towards the normative side of the spectrum, so maybe I’m misnamed the second component. But let’s see–what would we expect to have a lot of narrative besides novels?

Even with the double imperfections of a random starting point and just guessing at genre from titles, it’s definitely inching towards established categories. And this is certainly not “History” as we’d define it:

> sample(catalogtitle\[grep("history",catalogtitle)],5)

[1] “Thomas Carlyle; a history of the first forty years of his life, 1795-1835”

[2] “The pirate’s progress; a short history of the U-boat”

[3] “Common-law pleading : its history and principles : including Dicey’s rules concerning parties to actions and Stephen’s rules of pleading”

[4] “A history of the United States navy, from 1775 to 1893;”

[5] “Three visits to Madagascar during the years 1853-1854-1856. Including a journey to the capital; with notices of the natural history of the country and of the present civilization of the people”

So what? Is this only good for recreating genre I could get from the library? Not just that, if that will even work. Our established genres don’t always give us just what we’ll want. There are books of international law, and there are boy’s adventure novels. But it may be that someone will want to look at the language around ‘ piracy ’ at some point: the clusters that capture descriptions of marine settings would be more relevant than either of the established subgenres for that. Directed PCA and clustering is the key to figuring out how to create the dimensions we might want.

And can it tell us anything about history? Just to give a very fuzzy example, let’s ask a question that no one would ever ask–where does the phrase “natural selection” fall on a spectrum of personal vs. impersonal language? Does it change over time? Here’s a chart. (Not the right sort of chart, which would use cells, but a chart nonetheless). Each dot is a book: the red ones are those that use “natural selection.”

This is completely provisional. But it shows a few things. First, that there’s a historical pattern to the very vector I’ve chosen–there seems to be more of the very ‘ personal ’ language at the end. (Perhaps it’s also ‘ colloquial ’ language, or ‘ American ’ (vs. British) language, or something else?). With the red, we can see natural selection check in right in 1860 with discussion in more ‘ impersonal ’ books; then from about 1870, it is mentioned increasingly in both personal and impersonal books to about 1895, after which it falls off in both, but perhaps more in the impersonal language. All this is _very_ preliminary: but that might be more consistent with a story of rapid popularization after 1870 than one of gradual widening out from the scientific literature.

It certainly doesn’t prove anything, but I think there’s something to this method. Imagine if, say, instead of ‘ personal ’ or ‘ impersonal ’ words we had ones that were oriented to capture biological vs. political language, and we could compare a raft of words related to Darwinism to see which ones made the leap from the former to the latter. Are they the Darwinian terms that appear disproportionately in the works of Spencer? This could help to refine some quite fine questions about reception and distribution, as long as the library of books is a decent one.

Comments:

this is all pretty interesting stuff, but i say it…

Anonymous - Dec 3, 2010

this is all pretty interesting stuff, but i say it’s a red herring and what you all should really be pursuing is better meta-data if you can get it.

what’s the plan on that? are their cooperative database projects you could hook up with?

Two questions: 1. How did you decide which words…

Jamie - Dec 4, 2010

Two questions:

How did you decide which words to use for PCA? Did they come from that bookcount v. wordcount spread? And when you move to a biological/political distinction, how would you choose then?

What makes “the” narrative rather than “normative”?

This is very cool stuff. I’m looking forward to seeing you refine and elaborate it.

1. This time, I’m just using the 100 most comm…

Ben - Dec 4, 2010

This time, I’m just using the 100 most common words for PCA. I’ve been thinking about using that spread, though, or maybe finding a different index of the dissimilarity of words based on their distribution across books. For choosing a biological/political distinction, I’m not totally sure–either I’ll have catalog data by then and could just move out from the words most different between the two call numbers; or I’ll just intuit some biological words and then use searches to find words that are particularly closely tied, something like I did for scientific method except actually pulling the words out of the last cloud.

Nothing. PCA is not choosing categories that actually map on to semantic ones. But sometimes you can intuit that they’re close because so many of the patterns that structure authorial word choice are semantic ones. So provisionally, I’m just using some to pretend the results make semantic sense. But in fact, they’ll never actually correspond to meaning all _that_ well.