Canonic authors and the pronouns that they used

My last post had the aggregate statistics about which parts of the library have more female characters. (Relatively). But in some ways, it’s more interesting to think about the ratio of male and female pronouns in terms of authors whom we already know. So I thought I’d look for the ratios of gendered pronouns in the most-collected authors of the late 19th and early twentieth centuries, to see what comes out.

On the one hand, I don’t want to claim too much for this: anyone can go to a library and see that Washington Irving doesn’t write female characters. But as one of many possible exercises in reducing down the size of the library to rethink the broad aspects of the literary canon, c. 1910, I do think it’s suggestive; and, as I’ll suggest towards the end, knowing these practical details can help us explore the instability of ‘ subject ’ or ‘ genre ’ as expressed by the librarians who choose where to put these books on the shelves.

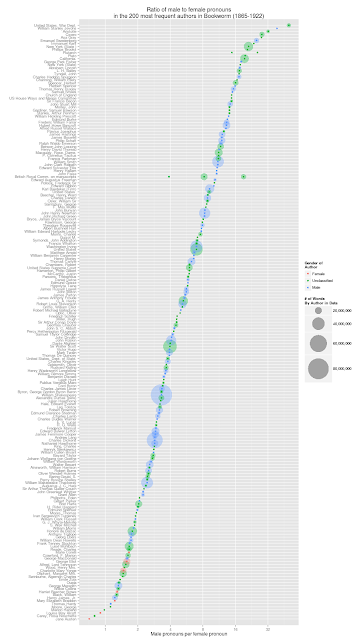

To start: here’s a chart that shows the gender ratios of how many times authors use male pronouns (he/his/him/himself) over how many times they use female ones (she/her/hers/herself). The colors show the machine-derived author gender based on first names.

*Except for George Eliot. I changed her by hand to female a while ago. That was, though, a poor choice I’m going to rectify eventually. I’m eager to hear if there are more male pseudonyms for female authors shown here, but I’m not going to change any more of them because the presumptive gender of the pseudonym is every bit as interesting as the physical sex of the author. Ideally, of course, I’d have both.

These are the 100 authors with the highest number of personal pronouns in the Bookworm database The circles sizes are the number of pronouns used. Right in the middle is William Shakespeare, for example: his dot is the largest because there are multiple copies of most of his plays, and he’s in the middle because he has approximately the same overall gender balance as the whole corpus. (Over three male pronouns for every female one).

This is interesting for two reasons. First, it gives you some of the most common authors in 19C libraries:* that’s a list which has some interesting contrasts with who we think of as the canon. Washington Irving is quite a bit better represented than I would have thought, for example. Second, it lets us compare those authors to each other in a relatively straightforward way. Henry James writes a lot of female characters, but he still has about 20% more male pronouns. Emerson really never mentions women.

*[Edit–most common just by the number of pronouns they use, which, as John Theibault points out, isn’t the same as the number of words they use. For the top 200 authors by overall word count, see the bottom of this post].

The most blaringly obvious thing here is that almost all the female authors are down towards the lower left. There are only four authors out of the top 100 who have more female than male pronouns: all are women. Austen and Alcott everyone knows; Gaskell wrote North and South, which I’ll write about at some point on my TV blog; Rosa Carey (who the classifier stutters out on, because the Open Library put her last name first in the ‘ author ’ field) wrote girls’ novels.

Genre is playing a big role here. I can group each author by the LC classification under which they published the most books: it doesn’t always work (Grant Allen was more a science writer who penned novels than the other way around, Samuel Smiles is there for self-help), but it helps put some order on all the names you might not recognize.

The thing that really comes out here is the distinction between PZ and PS: there are far more women writing in PZ (Fiction and juvenilia) than in PS (American Literature). And there’s not really a difference between the two: that Louisa May Alcott is a juvenile writer and James Fenimore Cooper a literary writer presumably has as much to do with gender as with content. The center of the curve skews more female in in PZ as well.

That highlights one of the most important things to keep in mind when doing this sort of work: that it’s a convenient abstraction that gender and classification might be two different things, but in fact gender is so important that we have to assume it bleeds over into other form of classifications. This is one of the great problems with using established libraries (because they are “biased”) but also one of the opportunities, because we should be able to see some of the ways bias is instantiated into categories.

Two last charts, and then I’ll move onto other things. First, I was showing only the top 84 out of 1,000 authors: there are actually 25 who show include more female pronouns than male, so I’ll pull them out so we can see just who they are.

Again, it’s mostly women: there are a few men in there, too. (Although some of them are strange: Jean-Henri Fabre makes the cut because he refers to spiders as “she”).

One last question might be: given that we know there’s a baseline for pronoun use by gender and subject, can we tease out which authors are most remarkable in their context? Just a linear model across the five most common classifications allows this: in the following chart, Hardy and James occupy the far left as the authors who use far more female pronouns than their genre (literature, PR or PS) and gender (male) would have us expect.

Does that mean anything? I really don’t know–possibly not. Certainly not if done in some abstract competition for ‘ credit. ’ But it’s interesting to see that Marie Corelli was a remarkably male-centered author for her gender, or to see James Fenimore Cooper somehow manage to appear to the female side of the spectrum for a man writing “American literature” (PS).

It seems to be that it might be generally interesting to be able to compare authors across a wide range of word metrics like this, so we could see if statements about an author’s linguistic peculiarities are actually true. This is something we could currently support in some form with the Bookworm API–it’s possible this would be useful for something out there that isn’t the problem of author gender or pronouns. It’s worth thinking about.

[Edit]: Here’s the top chart done for the top 200 authors overall, not restricted by pronoun count. Click to enlarge.

Comments:

Unknown - Feb 4, 2013

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

One quick question/clarification. You say “Th…

john theibault - Mar 1, 2013

One quick question/clarification. You say “These are the 100 authors with the highest number of personal pronouns in the Bookworm database.” But later on you imply that they are the “most common authors.” There’s no reason to think pronoun use corresponds with commonness. Have I missed a step somewhere?

Yeah, this was a bit sloppy on my part; I’ll p…

Ben - Mar 1, 2013

Yeah, this was a bit sloppy on my part; I’ll post some revised charts if I get a chance. Pronoun use corresponds with commonness roughly within literature (just like use of ‘ the ’ and ‘ in ’ corresponds to length–it’s just that common) but I’m definitely dropping some authors (William Graham Sumner, say) who just don’t use pronouns that much from the charts. I did that because I liked having it skew toward literature, but that isn’t especially defensible. The thousand author list I use for the penultimate count is based on total number of editions in the set.

OK, there’s a new bottom chart. It goes up to …

Ben - Mar 3, 2013

OK, there’s a new bottom chart. It goes up to 200 because that’s the cutoff to include Jane Austen, who is one of several literary figures who get bumped way up because of their pronoun rate.

Remarkably wonderful work

betsy McLane - Mar 3, 2013

Remarkably wonderful work

English Pronouns is very important because its str…

Julia Robert - May 5, 2014

English Pronouns is very important because its structure is used in every day conversation. The more you practice the subject, the closer you get to mastering the English language.

Subject and Object Pronouns