Bookcounts are in

I now have counts for the number of books a word appears in, as well as the number of times it appeared. Just as I hoped, it gives a new perspective on a lot of the questions we looked at already. That telephone-telegraph-railroad chart, in particular, has a lot of interesting differences. But before I get into that, probably later today, I want to step back and think about what we can learn from the contrast between between wordcounts and bookcounts. (I’m just going to call them bookcounts–I hope that’s a clear enough phrase).

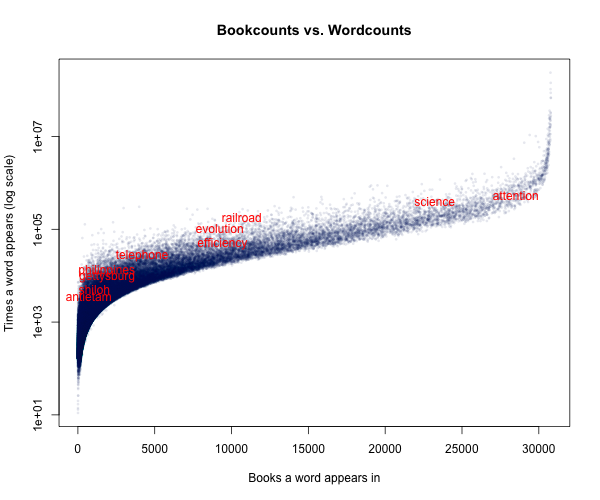

Roughly, wordcounts are how many times a word is said in my library, and bookcounts is how many different authors are saying it–or how many different readers are reading it. (Given prolific authors, multiple authors, etc. that’s not quite true, but it’s still an OK way to think about it). Since this is a quantitative blog, let’s start with a chart. Here are the two different counts simply plotted against each other (please someone e-mail me if these image files don’t come through as well as the earlier ones):

Each of the 200,000 points is a word–from “the,” all the way up in the upper right hand corner, to a whole morass of words we’ve all forgotten and typos, down in the lower left. The red line is the theoretical minimum– a word appearing in exactly as many books as is its word count.* This is abstract, I know, so let’s add some of the words we’ve already been analyzing to the chart to humanize it a little. (By the time we get through with this, my little linguistic studies the last few entries will have taken us back to history, I promise).

This is starting to tell us something. You can get a sense, looking at all the points, of what the overall curve is. (If you actually know the name of distribution, please please e-mail me right away–I want to fit a line to it, and I’m at the limits of my knowledge. I might just do another loess, but there’s definitely some logarithmic or polynominal or something function that will work better.)

Take “railroad,” “evolution,” and “efficiency.” All appear in roughly the same number of books–railroad in just over 10,000, evolution and efficiency in just under. But they appear dramatically different numbers of times – railroad appears 3.7 times as often as efficiency (note that the y axis is on a log scale). The places that railroads are discussed, they get mentioned a lot. For the record, ‘ telegraph ’ is at the same place as ‘ efficiency ’ on the scale; so it’s not about technologies vs. concepts or anything like that.

So what is it? Well, here’s another way of thinking about the difference between the two. There are seven words that appear between 181,500 and 182,000 times in my library: here’s how many different books they appear in.

absolutely rapid occasionally province india colonies railroad

24081 23437 22217 16776 16665 12128 10676

The first three are simply common words. The last four, though, are more interesting. Would anyone, besides the most committed imperial historian, have been willing to bet that ‘ colonies ’ or ‘ railroad ’ is as common a word as ‘ occasionally ’? I doubt it. It’s certainly not true anymore. And even back then, any given writer was more likely to pull ‘ absolutely ’ out of his vocabulary than ‘ colonies ’. But for historians, the last four words are far more interesting. The imperial overtones are mostly a coincidence, I think–but it’s clear that words may be, semantically, just more interesting as they occur in fewer books.

So why would words be concentrated that way? I can think of four reasons off the top of my head: please add some more in the comments.

Year. If you squint, you can see that most of the words we’ve been looking at are above and to the left of the main curve. That’s partly because we’ve picked out historically interesting words–that means that there are a lot of years where they aren’t used at all. I could make a chart like the above one, but only for the year 1910, say. If I did, I think much of the distinctiveness of a word like ‘ efficiency ’ would be lost, since it was a common vocabulary word then, unlike in 1850.

Monograph-icity. I’m not sure what to call this one, but it’s important. One of the things that makes a word like “railroad” stand out is that people actually write books about railroads, which use the term all the time. On the other hand, no one could write a book about “rapid”, and it’s hard to write a book about ‘ provinces ’ in general. Mentions of a word will cluster in particular books based on how intensively you can write about the concept it describes.

Genre. This is one that I’m really interested in. Some words are fairly specific to particular genres, and could even be used computationally to try to classify books according to genre. “Science” is one up there that’s relevant, but see below for a few more.

Data Problems. See below: tlie and tbe, our two most common typos, stick out on this chart. I’d guess that’s because they appear disproportionately in books printed in certain fonts. We could probably, in fact, use this data to reconstruct the font families of many of these books based on the OCR data. Maybe that’s my next blog.

About that genre thing–let me just leave you with one more version of the big chart at the top. Let’s zoom in on the top right corner, and only look at words that appear in over 18,000 books. And instead of representing each word with a point, we’ll actually put the words in. You look at the words that stick out to the left and above the main line, and then I’ll give my take.

The most common ones are interesting–you,her,my,she,your…. You, for example, is one of the most common words in the language, but there are about 1000 books that don’t use it even once. Clearly, this has to do with genre and stylistic conventions–certain authors never address their reader–and that’s going to be disproportionately common in certain genres. Likewise, ‘ she ’ and ‘ her. ’ There are a lot of books that never once have a feminine reference.

But the numbers on words like that are driven up _a lot_ somewhere, because the words are still very common. For “she” and “you” in particular, I’d wager that it’s the fiction that really restores women and the second person to their proper place in the language. I bet we could use some words like that as markers to judge what books are probably novels. (Maybe I’ll get more into how to do that–some combination of clustering and principle components analysis–later.) I think this could contribute to discussions about femininity and the novel. It might even be possible (I won’t do this, but maybe someone knows an English Ph.D.?) to extract everything within quotation marks in the presumptive novels, to analyze novelists’ changing representations of demotic speech. Wouldn’t that be fascinating?

But most (well, all) of my readers are historians, and you probably really got interested in the words a little farther down the curve. Particularly “government”, hanging out there like the moon in space. “Government” is discussed, that’s almost certainly telling us, fairly intensively in a number of books and not at all in some others. How is that distributed across the period? What are the other words in the books that use “government” disproportionately? I can see at least two other keywords from Dan Rodger’s second book, people, hanging out in our space temptingly, and of course there are a number of other political words out there as well–constitution, property, money. There are some semantic databases–even one right here at Princeton–that class words by category, I think. It might be interesting to study the differences in these.

And at the very left, about fourth down, is “species.” If I hadn’t started this project thinking Darwinism was a productive area of inquiry, this chart would have suggested it to me. Pretty cool. Can you see anything else on here that suggests other inquiries worth starting?

*(footnote from the third pp) Yes, I actually have a few words that fall below that theoretical minimum. They’re mostly typos for either high roman numerals, or for the word illustrated. It has to do with the way I do my total wordcounts–they ignore words that appear alone in a paragraph, which the bookcounts don’t. Here, we’re just catching some titlepage/table of contents errors. I don’t think it’s a big problem, although I should fix it.

Comments:

What about the words that fall right in the thick …

Jamie - Nov 5, 2010

What about the words that fall right in the thick of the curve? I’m thinking of “attention,” which in the second graph looks like it has an average word- to bookcount. It might be interesting to do a year-by-year look at how it settled into its place in the curve: was it originally used a lot in a few books? Or sparingly by a lot of books? That’s a basic how-does-it-change question.

Also, when a word is used about as often as you might guess, that’s probably good news for the philological/cultural analysis, since the question can open up to look at the words that surround the original word. Or to put it differently, I wonder if this gives you more permission to see semiotic changes in “attention” as significant.