Author Ages

Back from Venice (which is plastered with posters for “Mapping the Republic of Letters,” making a DH-free vacation that much harder), done grading papers, MAW paper presented. That frees up some time for data. So let me start off looking at a new pool for book data for a little while that I think is really interesting.

Open Library metadata has author birth dates. The interaction of these with publication years offers a lot of really fascinating routes to go down, and hopefully I can sketch out a few over the next week or two. Let me start off, thought, with just a quick note on its reliability, scope, etc., looking only at the metadata itself. The really interesting stuff won’t come out of metadata manipulation like this, but rather out of looking at actual word use patterns. But I need to understand what’s going one before that’s possible.

Open Library has pretty comprehensive metadata on authors. In the bigpubs database I made, about 40,000 books have author birth years, and 8,000 do not; given that some of those are corporate authors, anonymous, etc., that’s not bad at all. (About 1500 books have no author listed whatsoever).

First, a pretty basic question: how old are authors when they write books? I’ve been meaning to switch over to ggplot in R for basic graphing, so here’s a chance to break its histogram function. Here’s a chart of author age for all the books in my bigpubs set:

It peaks in the 40s (median 49), and has a long but quite small trail of republication going off into the hundreds, which are mostly posthumous republications. There are also a few books written by child authors that are almost all errors. You can’t see information on authors yet to be born, but there are a number of people publishing books at negative ages in the data as well. (Death dates may be worse: the first author I checked on their site was William James. He was listed as living from 1842 to 1827, until I fixed it.) These metadata problems, however, are quite insignificant compared to the data that we get. And the overall curve shows us something important: the vast majority of books in the Internet Archive are fairly new, not dusty reprints. That’s why this works so well, even including all the republications in the sample–because although a few authors like Shakespeare or Pope keep getting republished, most don’t.

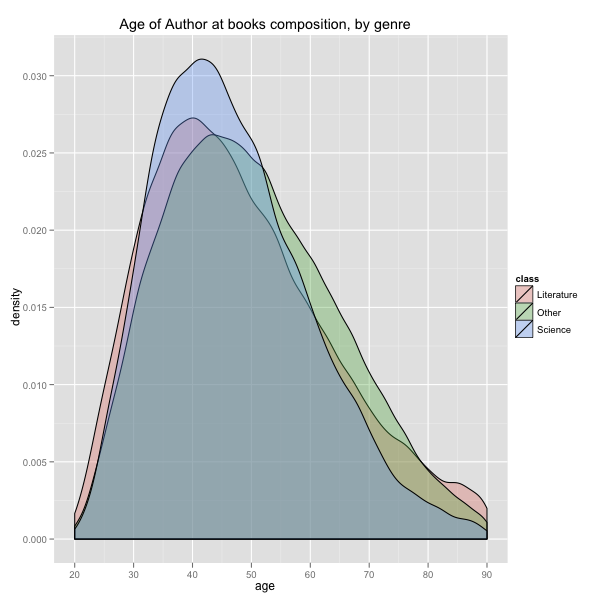

There’s genre variation in this. At one end, the LC subclasses for European literature, history of the low countries, and biography all have a median author age of 60; on the other, municipal government, motor vehicles and aeronautics, and military engineering all have median author ages of 38. Technology classes seem in general to have the youngest authors, history and religion to have the oldest. But that variation is pretty slim. Here, for examples, are the density curves (pretty much a smoothed version of the above chart) for three big groups: science and technology (LC classes QRST), literature (class B), and everything else (which ends up being mostly education, social sciences, and humanities). This is showing proportionately how concentrated these different fields are various ages, in pretty transparencies:

That’s saying that while they all peak in the forties, the sciences have a tighter structure: fewer young authors _and_ fewer old authors, while literature (red) has a lot more young guns as well as a lot more late republications, and correspondingly fewer of its books written by forty-somethings. The catchall ‘ other ’ category is the books I’m the most interested in, for the most part, and they tend to skew older–you can write a novel at 25, but even in the 19th century, evidently, people aren’t getting their history books out until their mid-30s.

But what’s most striking is just how similar they are. It would be interesting to see if we could find some axes—probably not LC classification—where there were really marked dissimilarities in author age

One last point: obviously no one is writing books at 110, but I am getting some of that stuff in the data.

Open Library maintains a separate database entry for works as well as for editions, that would let us lump every publication of Tom Sawyer back into 1880, or count just the first one. In library terms, it’s FRBR-ized a bit higher. About 9,000 of the 48,000 books in my corpus are duplicated works republished in a later year. But not everything has a work year, and just as some authors have negative ages, some books are published years before their “first publication.”

Can we use that information to get better information? I’ll keep an eye, but it makes surprisingly little difference at this level of aggregation. Most books that are republished, Open Library thinks, are republished only a year or two later. Using that data also induces some error for reasons not worth getting into. I might, quietly, shift over to that as my primary year information at some point instead of the year of publication data, but for now I’m not convinced that it’s good enough to warrant the increased complexity of explaining what it is. Year of publication works well enough. As evidence, here’s the same chart as above, but made using authors age at first publication. Where the above chart counts William James as 60 for an 1902 reprint of the Principles of Psychology, the one below counts that book as having a 48-year-old author since James originally wrote it in 1890. But as you can see, it hardly makes a difference: the science peak is even higher, but that’s the only big difference I can see:

Anyhow, enough of that. Next up is what author age can tell us about language.