Anachronism patterns suggest there's nothing special about words

I’m cross-posting here a piece from my language anachronisms blog, Prochronisms.

It won’t appear the language blog for a week or two, to keep the posting schedule there more regular. But I wanted to put it here now, because it ties directly into the conversation in my last post about whether words are the atomic units of languages. The presumption of some physics inflected linguistics research is that it is. I was putting forward the claim that it’s actually Ngrams of any length. This question is closely tied to the definition of what a ‘ word ’ is (although as I said in the comments, I think statistical regularities tend to happen at a level that no one would ever call a ‘ word, ’ however broad a definition they take).

The piece from Prochronisms is about whether writers have a harder time avoiding anachronisms when they appear as parts of multi-word phrases. Anachronisms are a great test case for observing what writers know about language. Writers are trying to talk as if they’re from the past; but–and this is fundamental point I’ve been making over there–it’s all but impossible for them to succeed. So by looking at failures, we can see at what level writers “know” language. If there’s something special about words, we might expect them to know more about words than phrases. But if–as these preliminary data seem to indicate–users of language don’t seem to have any special knowledge of individual words, that calls into question cognitive accounts of changes in language, like the one the physicists offered, that rely on some fixed ‘ vocabulary ’ limit that is enumerated in unigrams.

Anyhow, here’s the Prochronisms post:

This is technical, but I wanted to dig into something that Ben Zimmer said about my work on anachronisms recently in one of his columns about Lincoln.

One thing that is clear from Schmidt’s work is that while screenwriters (and audiences) may have a good ear for discerning when individual words are anachronistic, it’s less easy to pick out when combinations of words are unlikely to have been used in a historical setting.

I have believed this to be true, and written it from time to time. This was the reason I went with two-word phrases from the start. Recently, I’ve been adding in one- and three-word phrases as well, and I’ve noticed more mistakes on one-word phrases, and fewer on three-word ones, than I would have expected given this presupposition. And I’ve started to wonder if I was actually right about this: is it actually easier to get unigrams right than bigrams?

Back to basics. Why would we expect to see more writers getting longer phrases wrong to begin with? I can think of three reasons. The first two I’m almost positive are true: the third, I’m not.

There are just more multi-word phrases in any given script.

Multi-word phrases tend to be rarer, and rarer words are easier to get wrong than common words.

Changes in longer phrases are intrinsically harder to hear.

It’s the third that’s interesting: so I’m going to confirm the first two quickly, and then see if anything remains.

The first is definitely true: we can see it in”Downton Abbey.” There are about 1200 distinct unigrams to check in each episode, but about 3200 distinct bigrams and 2800 distinct trigrams:

[Why fewer trigrams than bigrams, you ask? Good question: there are two big reasons. First, I’m only plotting the words or phrases I could match in the Google Ngrams database, and plenty of trigrams (“Earl of Grantham,” say) just don’t show up in books enough to meet the cutoff. And second, I’m only checking strings of words not intersected by punctuation: so the line “Yes sir” will produce two unigrams, one bigram, and no trigram.]

The second possibility has two parts:

Multi-word phrases tend to be rarer, and rarer words are easier to get wrong than common words.

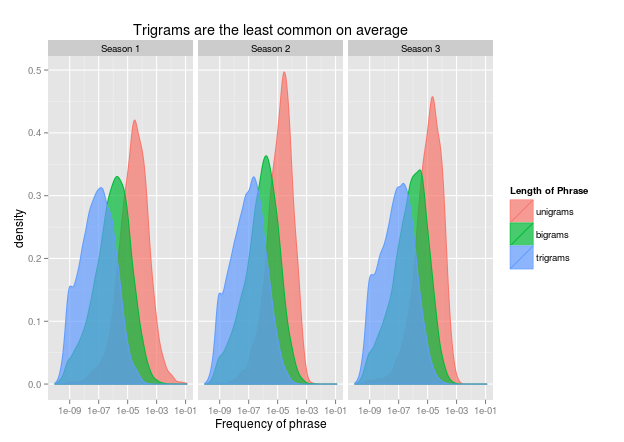

The first part is definitely true:

And next part is true with a caveat: it’s easier to get rare words wrong, but it’s also easier to get them right. They just have more variability. You can see this in the density plot–the red distributions (they look orange, but I think that’s just an optical illusion are squatter, which means that a rare word is more likely to be strongly anachronistic or strongly characteristic. This is mostly just gaussian distributions, I think: if the overall sample of words in ngrams were 100 times larger, all of these curves would probably be tighter. But there’s also likely a cognitive component on the anachronism side (anachronisms are more common than highly characteristic words): as words are rarer, writers are less likely to know.

So that takes us to the last question: is there something actually linguistic about the change, or is it just these statistical distributions that mean so many more multi-word phrases are wrong?

One way to answer this would be just to take the two above charts and combine them. I’ll drop out the season faceting.

This is actually incorrect. Simply binning into quantiles is vastly misleading: since unigrams are more common than bigrams, within each quantile the unigrams still tend to be more common. So these bins aren’t actually comparable across word length.

The right way to check this is to use the same sorts of plots I’ve been making all along.

Here you can see that the shapes for each cloud is similar, but that blue and green are denser and have fewer very common words. I’ve also added some loess smoothing lines, but you can barely see them. If I take the lines out, though, we can finally get the desired comparison. Drumroll…

Surprise! It’s that individual words are actually more likely to be anachronistic than trigrams or bigrams for any given frequency.

That’s really surprising to me, and I can’t see any immediate reasons why it would be false. I checked capital words, which I thought might make a difference: the only big desideratum I can think of right now has to do with compound words and other spelling changes. I’ve been building up a list of words to exclude (“anyone” is anachronistic in print because of “any one,” for example) but I haven’t done much with spelling changes that only get slightly more common. So maybe those are more common in the unigrams (although I’m not sure they should be). I can’t quantify whatever that effect is right away: there’s a chance it’s so large that it overwhelms a real ability English speakers have to tell when unigrams sound anachronistic. And there might be something else I’m not seeing right away.

But for now, I’m left with no evidence to speak of that it’s actually any easier to situate individual words in their time than it is to fit in bigrams. That’s surprising, and sort of interesting. (Even though, for the first two reasons, most of the mistakes any given writer makes will be bigrams). I can’t say the scripts I’ve looked at make that seem ludicrous: Tony Kushner said he used the OED for any questionable word in Lincoln, for example, and still ended up with several words that the OED definitively says he shouldn’t have.

On the other hand, this is tentative. (Among other things, I’m purely investigating Julian Fellowes here: although I haven’t seen strong signs he’s qualitatively different in his anachronisms from anyone else).

But also, it might make some intuitive sense: screenwriters imaginatively project themselves to write historical dramas, and when they do so they don’t speak it a word at a time, they speak it in sentences. Most of the time, they don’t use a dictionary or any other source that handles unigrams better than bigrams: so why would we really expect them to be any worse at single words?